Global Risk Perspectives - Monthly insights on geopolitics, trade & climate

Back to articlesBernardo Pires de Lima

29.04.2022

Five Dynamics that Will Shape the Decade

Throughout this now protracted phase of systemic shocks, first caused by the pandemic and then the Russian invasion of Ukraine, there have emerged at least five trends that will make a mark on international politics over the next few years. Some signs are already plain to see.

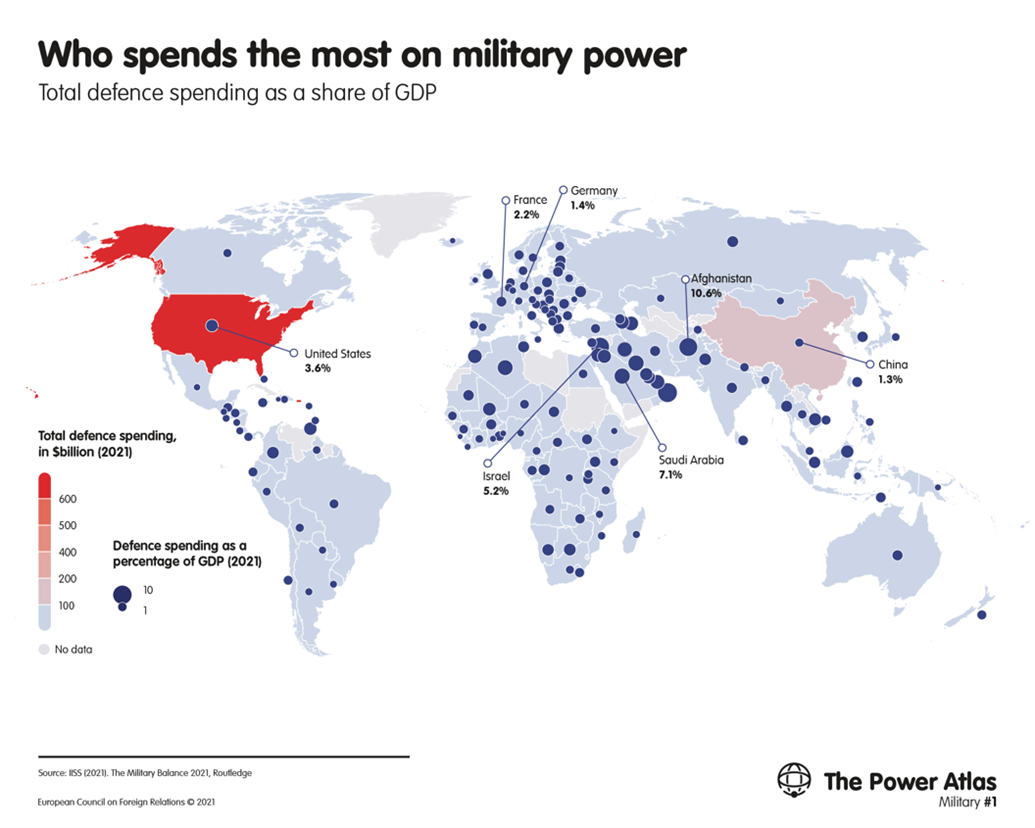

The first dynamic arises from geopolitical competition among great powers. The compatibility (or lack thereof) among assumed power echelons, like the status quo derived from the American unipolar age, or the state of things caused by Russia's ambitious play for parity based on imperialistic revisionism, and the one arising from China's multiple unique capabilities, which is yet to be clearly defined as to the geography of China’s strategic interests, and the one structuring India's multiple advantages, in a gamut of partnerships that aren't necessarily compatible. Add to this inharmonious quartet whatever clarification of power the EU brings to the table and, finally, the consolidation (that may or may not happen) of several regional powers in Africa (Nigeria, Egypt, South Africa), Latin America (Brazil, Mexico, Colombia) and Southeast Asia (Japan, South Korea, Indonesia). We must ask ourselves what sort of international order will accommodate this puzzle and wonder as to the modus operandi that will govern their relationship, whether they have nuclear capabilities or not. It is not yet clear how the game will play out, but signs point to a level of confrontation at trade, ideological, energetic and technological levels. Heightened concerns over military action are justified.

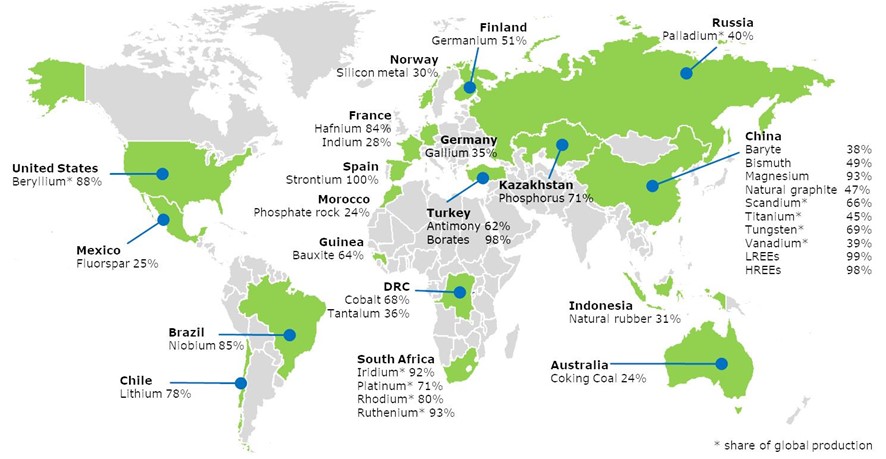

The second dynamic originates with technological competition between the great powers and small or mid-sized countries rich in mineral and energy resources. Digital transformation of economies, accelerated by the pandemic, coupled with the need to rebuild production and supply chains that are cheaper, more predictable and sustainable, already pushes to the fore new extraction needs based on the current stage of economic globalization (lithium, nickel, bauxite, manganese, and more). Cooperation or confrontation around such resources will shape the level of internal conflict in countries affected by unreliable government as well as the level of ecological degradation they are willing to accommodate. Technology and energy are therefore the drivers of a global economic transition among those on the leading edge and those at risk of falling behind. The regulation of behaviours and, most of all, impacts, will be fundamental to international security and stability.

Source: European Commission report on the 2020 criticality assessment

The third is competition for water — either for its relevance to economic sustenance and social stability, or access to seas and oceans as lanes for global shipping, as is the case of navigability in the emerging Arctic route, or the connection between the Black Sea and the Mediterranean through the heavy traffic of the Bosporus. Not that this topic is exactly new — it was the subject of deeper analysis in this series, last January — but, at present, 40% of the world's population faces water scarcity, which will cause the involuntary displacement of 700 million people by 2030. So-called hydro-politics is a subject of extreme contention in the light of concerning levels of global warming, rising ocean levels, prolonged droughts and conflict-prone management of the flow of some rivers of vital interest to African, Middle Eastern and Asian economies — rivers like the Nile, Tigris, Euphrates, Yellow River, Yangtze, or the Mekong.

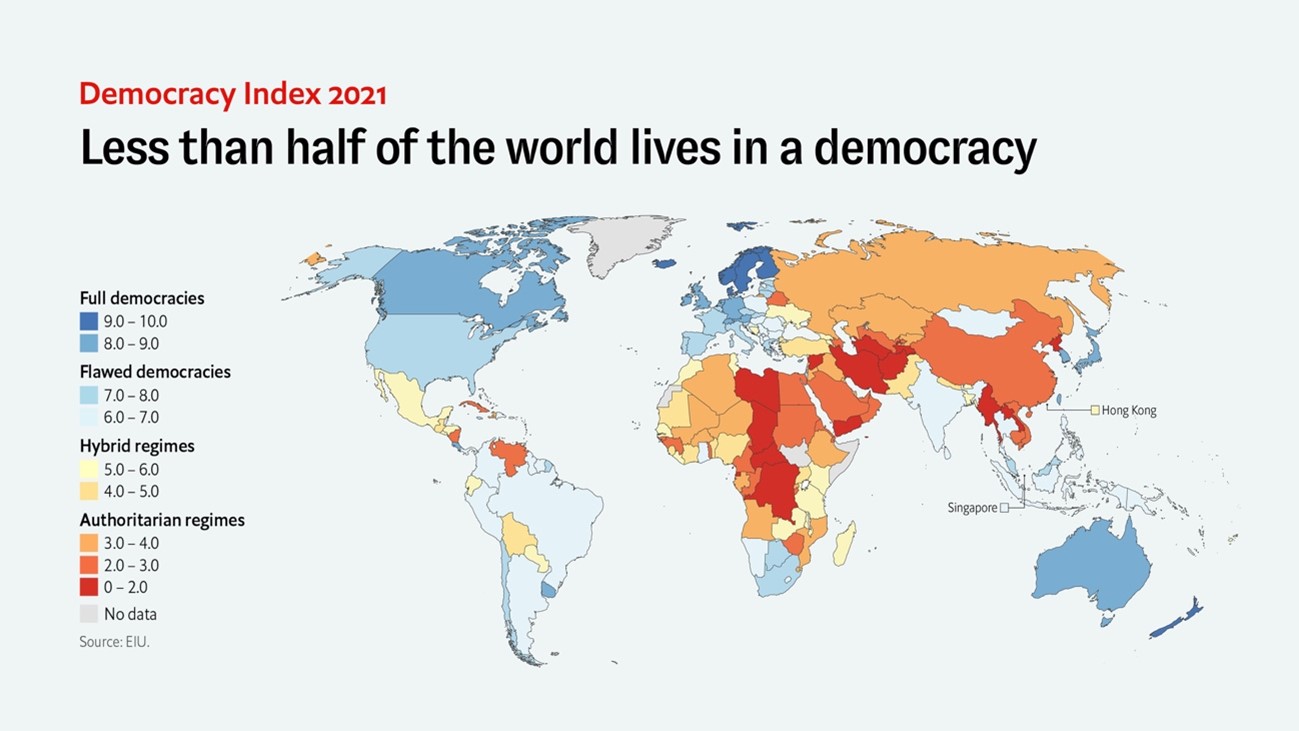

The fourth dynamic stems from the clash between democracies and autocracies. For the first time in the twenty-first century, autocracies represent the majority of political regimes. Pressured internally by top-down movements, histrionic populism, aggressive nationalism, ideological entrenchment, discredited institution, crystallized inequality, and decline of traditional media, democracies need to look to their health so that the cancers within them will not metastasize. Beyond the walls of democracy, the revisionist history of influential autocracies, alongside a concentration of power compatible with growing accumulation of wealth, have provided these regimes with the kind of trust that not only inspires many regions in the world but also call into question the merits of democracy, pluralism, separation of powers and respect for liberties. The conflict dynamics between these two models and the way some of its anathemas will be overcome will dictate the sustainability of democracies as we've known them.

Source: Economist Intelligence Unit

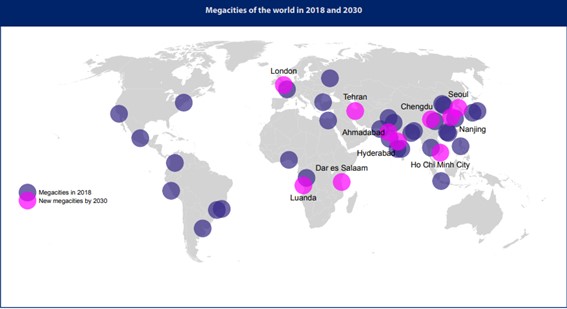

The fifth dynamic is demographics. The world's population is on the rise: we were 7.6 billion in 2021, and expect that number to go up to 8.6 in 2030. At the end of that decade 75% of the world's population will inhabit megalopolises with over 10 million residents, located mostly in Africa and Asia. This inflow of people is already straining major cities’ capabilities to house and integrate them, as well as coordinated responses from education, health and transportation services and, of course, creating environmental impacts that need containment if we are to hold back alarming global effects. Several tiers of policy reactions to these variables also entail permanent budget availability and even the international rise of governors and mayors as central political figures in globalization, vying with heads of state and cabinet leaders for protagonism.

Source: United Nations, The World’s Cities in 2018 report

Anticipating trends by monitoring signals that have stabilised over the short term is an imperative for the quality of public policy, levelling of inequalities, social and territorial cohesion, and also a better-articulated, predictable relationship between one nation and the next. Without that effort, systemic shocks are a given, risks for corporations will go through the roof and social and political volatility will become commonplace.

Disclaimer: Bernardo Pires de Lima, research fellow with the Portuguese Institute of International Relations (Instituto Português de Relações Internacionais) at Nova University of Lisbon.

The views, thoughts and opinions expressed herein belong solely to the author and do not reflect the official positions or policies of, or obligate, any institution, organization or committee he may be affiliated with.

Bernardo Pires de Lima was born in Lisbon in 1979. He is a research fellow at the Instituto Português de Relações Internacionais (Portuguese Institute for International Relations) within Nova University of Lisbon, international policy analyst at Portuguese TV network RTP and radio station Antena 1, political consultant to the President of the Portuguese Republic, chairman of the Curators Council of the Fundação Luso-Americana para o Desenvolvimento (Luso-American Development Foundation), and an author, having published, among other titles, A Síria em Pedaços, Putinlândia, Portugal e o Atlântico, O Lado B da Europa, and Portugal na Era dos Homens Fortes. He has been a visiting fellow at the Center for Transatlantic Relations at Johns Hopkins University in Washington DC, associate researcher at the Portuguese National Defence Institute, columnist for newspaper Diário de Notícias and a commentator at TV network TVI. Between 2017 and 2020, he led the political risk and foresight practice at FIRMA, a wholly Portuguese investment consultancy. He's lived in Italy, Germany and the US, but he keeps coming back to Portugal.