Global Risk Perspectives - Monthly insights on geopolitics, trade & climate

Back to articlesBernardo Pires de Lima

23.03.2022

War in Ukraine and Crises across International Economies

An Energetic Security Crisis

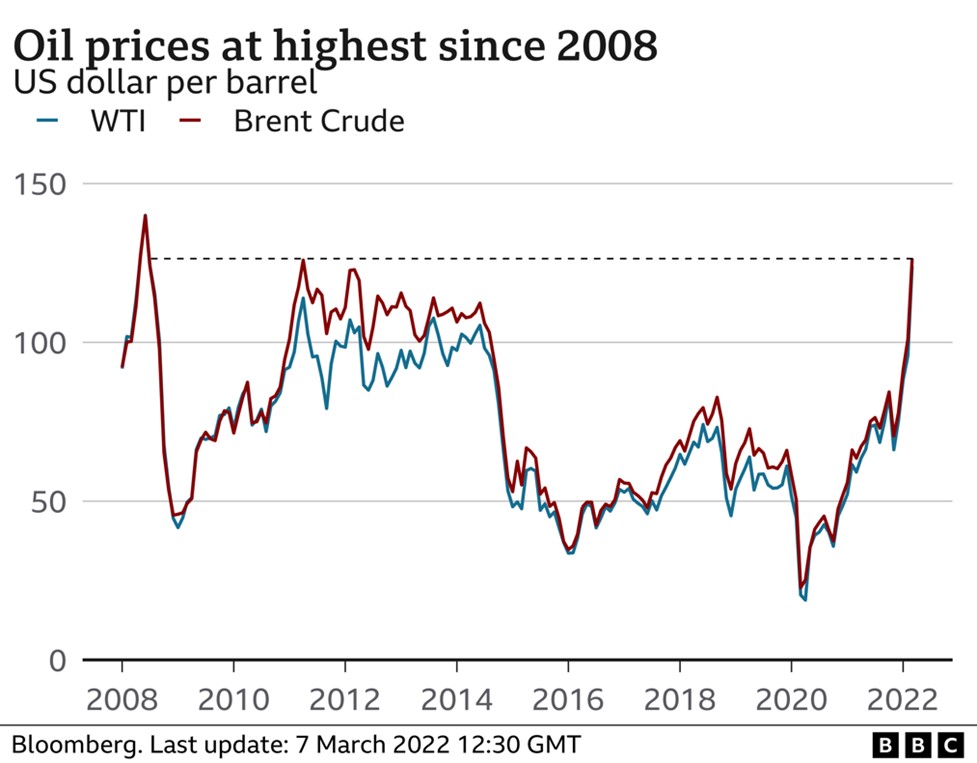

Soaring prices for energy and raw material predate the war in Ukraine. So it is worthwhile to add some temporal context. Let us say the starting shot was fired summer last year. Economic recovery, with its Asian epicentre, in a context of post-pandemic relief, had led energy demand to spike, especially for natural gas, a preferred resource for economies looking to decarbonize and electrify, where the weight of renewables remains of negligible significance. The absence of supply to meet demand levels, coupled with disrupted supply chains worldwide, delays in pipeline maintenance and power-maxing moves by some producers (most of them Russian), have led to a fivefold increase of gas prices between April and November 2021.

Intermittent lockdowns, scarcity of raw materials and semiconductor chips, the price of neon, indispensable to chip-making, shooting through the roof (by 600%), with over 50% of global exports coming from Ukraine and Russia, the steep price increase of fundamental raw materials (steel, aluminium, copper, wood, paper) and maritime freight, as well as choke points in global value chains, disruptions to logistics routes, accelerated global demand, and financial options that maintained a tax burden on some of these essential products, were the key reasons why costs went up for companies, industry, governments and families across the world. Globalized profit implies globalized cost when economies are so closely interdependent and value chains across industries carry impacts from the starting point all the way to the consumer.

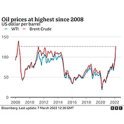

However, war in Ukraine and spiralling international economic sanctions against Russia, especially those aimed at Russia’s Central Bank, exposing Russian isolation and leading to the general pull-out of almost every foreign corporation operating in the country, have created worldwide tensions with ramifying impacts. Within a week, oil prices went up by 22%, to amounts per barrel unseen since 2008, the year of the Georgian war, likewise provoked by Putin's Russia. Subsequently, natural gas went up by 79% before the US announced its energy embargo. To make up for it, the US and other key global producers must increase their offerings to correct prices. Natural gas has surpassed all previous records, coming to a staggering 345 MWh, which reflects on wholesale markets in Europe as prices move skyward. The impacts eat deep into aviation and maritime transportation where energy represents 30% to 50% of overhead, but no less into car manufacturing operations, already stressed by the ascending cost of aluminium — around 100% last year — of which Russia is the second largest exporter.

All of this will force governments to intervene in order to mitigate the costs of energy for families and companies. The economic response to this new juncture, which will depend not only on the duration of this war, but also on the terms of future peace, is extremely demanding at a time when economies attempt to normalize their procedures after two years of a pandemic. Many of them are held back by chronic imbalances in their societies. In that light, stagflation in Europe could bring back another year of the budgetary rules written into the Stability and Growth Pact, and motivate the Central European Bank to retain the extraordinary stimulus policies launched during the pandemic, which may impact management of inflation, which is itself rising, and may drive up interest rates, impacting economic performance.

A Food Security Crisis

Once again, the rising cost of foodstuffs predates the war in Ukraine, but the conflict has not only sped up inflation but injected new levels of anxiety into the whole sector. And there is cause for concern. Ukraine and Russia represent a third of the world's wheat exports. Disruption to market access, blockages of ocean transport between the Black Sea and the Mediterranean and the absence of a regular transition between harvest seasons could devastate the value chain from end to end. In Ukraine, the most productive agricultural areas are under Russian fire: Kharkiv, Chernihiv, Poltava or Zhitomir. Production and supply numbers for wheat, sunflower oil, barley and other grains are already dipping between 10% and 50%. This is only going to get worse as the conflict draws on. If you add the fact that Belarus is one of the world's largest producers of potassium, a fundamental commodity for making fertilizers employed in agribusiness, and that the country is likewise targeted by economic sanctions, that’ll give you a clearer picture of the global issue.

For which reason it is relevant to go back to 2007/8, when rising prices of staple foods triggered protests in over forty countries, or when a new price hike in 2009/2010 inflated the cost of living in North Africa and the Middle East, leading to social upheaval that would feed into political revolt degenerating into civil wars. Such was the Arab Spring and the drawn-out conflicts in Syria, Yemen or Libya, whose food security is absolutely critical to social peace and employment stability. Currently, Lebanon buys 90% of its wheat from Ukraine (as does Moldova); Somalia, 55%; and Libya, 45%. Turkey imports 70%, and Egypt 65%. Explosive inflation on essential alimentary products is the stuff of nightmare for governments in those countries. That was one of the reasons (coupled with police violence) why Mohamed Bouazizi, an itinerant salesman from Tunisia, immolated himself at a square in the country's capital back in 2010, sparking the wave of protests that would one month later depose president Ben Ali, who’d been in power for 23 years.

An Infrastructure Security Crisis

Energetic, food and security vulnerabilities in Europe, exposed to unique levels of jeopardy by the Russian invasion of Ukraine, are already driving Europeans to strategic choices. The first is to pull back from dependence, diversifying sources of energy, and looking for different vendors and infrastructure. Germany has announced the building of two LNG terminals in the north of the country, which would constitute a preferential gateway for North American exports. The same could be achieved at the Portuguese harbour of Sines, if its renovation is provided with Iberian links running all the way to the heart of Europe and full capacity is deployed for its liquefied natural gas terminal, serving both trans-Atlantic and African business. Add to that a new network of gas pipelines and lanes connecting the Baltic and Adriatic, precisely to whittle away at Russia's footprint in Europe. Which is to say sea ports and gas lines will certainly form a part of Europe's strategy and companies will be watching both for business opportunities and mitigating measures for inherent systemic risk. The same must be said of other kinds of critical infrastructure, such as those that make cyberspace such a desirable vector of attack, with high cost and disruption potential to economic normalcy, and the undersea cable network that underpins all the digitization of our lives. On that topic, let us remember the vulnerability of governments to Big Tech: of the nine major undersea cables that crisscross the Atlantic, Google controls seven in whole or in part, and Facebook partially controls two.

Faced with many-layered threats, we will witness an evolving European debate on the path to diversified strategic autonomies. There will be no consensus. It will not happen overnight. But it points to greater endogenous capabilities in industry, technology, energy, health, transportation, logistics, agriculture, defence, and diplomacy. If the pandemic shone a stark light on the need to invest more, and more wisely, on some of these areas, then the war in Ukraine compels us to scrutinize others responsibly. The problem is we must deal with all of it under the yoke of stagflation. At any rate, the time we thought we had to defer major strategic decisions on our collective future now dwindles before our eyes.

Bernardo Pires de Lima was born in Lisbon in 1979. He is a research fellow at the Instituto Português de Relações Internacionais (Portuguese Institute for International Relations) within Nova University of Lisbon, international policy analyst at Portuguese TV network RTP and radio station Antena 1, political consultant to the President of the Portuguese Republic, chairman of the Curators Council of the Fundação Luso-Americana para o Desenvolvimento (Luso-American Development Foundation), and an author, having published, among other titles, A Síria em Pedaços, Putinlândia, Portugal e o Atlântico, O Lado B da Europa, and Portugal na Era dos Homens Fortes. He has been a visiting fellow at the Center for Transatlantic Relations at Johns Hopkins University in Washington DC, associate researcher at the Portuguese National Defence Institute, columnist for newspaper Diário de Notícias and a commentator at TV network TVI. Between 2017 and 2020, he led the political risk and foresight practice at FIRMA, a wholly Portuguese investment consultancy. He's lived in Italy, Germany and the US, but he keeps coming back to Portugal.

Disclaimer: Bernardo Pires de Lima, research fellow with the Portuguese Institute of International Relations (Instituto Português de Relações Internacionais) at Nova University of Lisbon.

The views, thoughts and opinions expressed herein belong solely to the author and do not reflect the official positions or policies of, or obligate, any institution, organization or committee he may be affiliated with.

Bernardo Pires de Lima was born in Lisbon in 1979. He is a research fellow at the Instituto Português de Relações Internacionais (Portuguese Institute for International Relations) within Nova University of Lisbon, international policy analyst at Portuguese TV network RTP and radio station Antena 1, political consultant to the President of the Portuguese Republic, chairman of the Curators Council of the Fundação Luso-Americana para o Desenvolvimento (Luso-American Development Foundation), and an author, having published, among other titles, A Síria em Pedaços, Putinlândia, Portugal e o Atlântico, O Lado B da Europa, and Portugal na Era dos Homens Fortes. He has been a visiting fellow at the Center for Transatlantic Relations at Johns Hopkins University in Washington DC, associate researcher at the Portuguese National Defence Institute, columnist for newspaper Diário de Notícias and a commentator at TV network TVI. Between 2017 and 2020, he led the political risk and foresight practice at FIRMA, a wholly Portuguese investment consultancy. He's lived in Italy, Germany and the US, but he keeps coming back to Portugal.