Remember the Cold War? The bi-polar world was a such a ‘simple’ time in which much of what happened could be framed within the context of the two superpowers facing off against each other.

Then, after the fall of communism 1989/91 there was a naive belief that liberal democracy would spread around the world. Instead, we are in a multi-polar period in which many of the fissures the Cold War had papered over have been laid bare.

Now there’s a lot of jostling for position as countries seek to gain advantage ahead of what might become a new Cold War between China and the USA which will force many of them to take sides. There’s also a darkness as authoritarianism again stalks parts of the globe challenging the idea that freedom is the best method to govern complex societies.

To better understand the complexities of the multi-polar world we need to know a country's politics. But we also must know of the mountains, rivers, seas and concrete around them to understand some of the forces playing their part in determining events. The starting point is a country’s position in relation to neighbours, sea routes and natural resources all of which have helped shape its history and how its people view the world. The actors on the world stage change, but the stage remains much the same. Egypt still requires the Nile to survive. The Himalayas still stand.

Maps reveal as much about a government’s strategy as any highpowered summit, or overly blown rhetorical speech. If you want to go somewhere, you can only start from where you are. That may sound obvious, perhaps trite, but a government or a leader forgets it at their peril. They must understand exactly where they are and how much fuel they have in the tank – Napoleon was not the first or last to forget the lesson.

The crisis over Ukraine reminds us of the effect geography has on events, and how the history of those events plays a role in how leaders think. All Russian leaders involve themselves in the immediate territories west of Moscow because it is mostly flat land through which Russia has been invaded or through which it heads westwards. What happens in Ukraine is of huge interest to Washington DC, Berlin, London, Paris, Warsaw, Moscow and elsewhere.

The North European Plain stretches from France to the Urals and is mostly flat. Its narrowest point is between the Baltic Sea and where the Carpathian Mountains begin. That place is called Poland. In previous eras Russia has moved westwards and plugged the gap through occupation or domination. Now the gap is open. With or without Putin as leader, Russia will never be reconciled to the loss of Ukraine. Having been invaded so many times via the land to its west, Russia views the region as a buffer zone between it and potentially hostile forces. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union Russia believed the former eastern bloc countries would remain neutral. Moscow was horrified as it watched state after state elect governments bent on joining both the EU and NATO. In 2014 its view of the Ukrainian revolution, which overthrew a pro-Western president, was that it was a coup designed to eventually bring NATO forces to the Ukrainian/Russian border.

The crisis over Ukraine reminds us of the effect geography has on events, and how the history of those events plays a role in how leaders think.

Geography is also partially behind the marriage of convenience between Presidents Putin and Xi. Both believe that together they can create a world system based on spheres of influence. If so, the Americans can be pushed out of eastern Europe and the western Pacific.

China and Russia view the post WWII world order as biased against them. Both believe the post-Cold War era left the USA as too powerful and talk about ‘unipolarity’ being unfair and dangerous for peace. Instead, they argue, great powers should accept that each holds sway in its sphere and will not interfere in others. They also rail again the idea of ‘universal values’ instead making the case that different civilisations develop different values and it is not for outsiders to try and influence them.

China and Russia are not normally allies. During the Cold War they were at each other’s throats over which system was the best form of Communism. They even came to blows over it in a sevenmonth long border skirmish in 1969. Nixon and Kissinger spotted the gap and widened it to weaken the Soviet Union. Putin and Xi now see the opportunity to weaken the Americans.

Their relatively new friendship will not last and both leaders will be aware of Lord Palmerston’s quote about ‘no eternal allies’ only eternal interests. Indeed, they have their own boundary disputes which can be brought up at a time of Beijing’s choosing. The 1969 border clash took place along the Ussuri River on a border drawn up the previous century when Russia forced China into ceding 65,000 square miles of territory east of Manchuria. Russia gained a long Pacific coastline including the city of Vladivostok then known as Haishenwei (The Bay of Sea Slugs). The Chinese still view the agreement as unfair and although the issue was settled decades ago it can be ‘unsettled’ if it suits Chinese politics.

Another clear example of geographies role in history is Australia. Once in the middle of nowhere, now a very big somewhere, and centre stage. It may be the 6th largest country in the world, but a severe lack of water in most regions means it can’t sustain a large population which in turn limits the size of its navy. And if a country the size of a continent can’t robustly defend its coastlines and supply routes – it better have a friend who can. Once it was the UK, now it is the Americans.

This way of looking at international relations is not enough in itself, but its an essential starting point. Understanding the geography of a place helps us understand both its history, and present, and how it might act in the future.

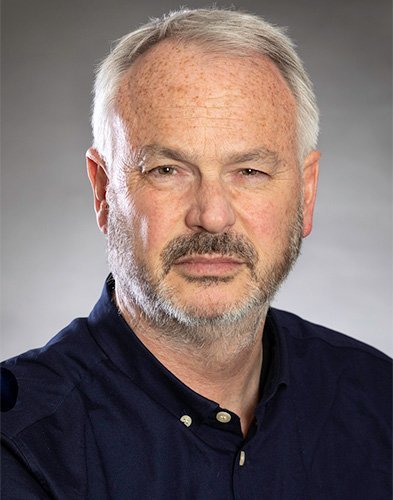

Tim Marshall's 2021 poignant new book

In 2021 Tim Marshall published The Power of Geography: ten maps that reveal the future of our world, the highly anticipated follow-up to his New York Times bestseller Prisoners of Geography.

In his new book, the author takes us on a tour of places — Australia, The Sahel, Greece, Turkey, the UK, Iran, Ethiopia, Saudi Arabia, Spain, and Space - that he considers pivotal to global politics and conflict - explaining how a region’s geography and physical characteristics affect the decisions made by its leaders.

Through ten chapters Tim Marshall explains why the Earth’s atmosphere is the world’s next battleground; why the fight for the Pacific is just beginning; and why Europe’s next refugee crisis is closer than we think. A compelling read, this book explores the power of geography to shape humanity’s past, present, and—most importantly—our future.