Global Risk Perspectives - Monthly insights on geopolitics, trade & climate

Back to articlesBernardo Pires de Lima

23.02.2022

Putin, a predictable strategist?

Russia, like Turkey, has been a part of Europe's modern history since the time of principalities, empires, nation-states, and it now finds itself among current integration models. Europe is the playing field for its geopolitical stances, even if Russia's strategic cunning keeps it apprised of threats and opportunities from Asia.

Russia is the most predictable of all major contemporary powers. Its body is overwhelmingly Asian, but the head of the beast bites deep into the European continent. It finds itself humbled, abused, despoiled and despised by its former peers in the struggle of geopolitics. Russian exceptionalism is paradoxically conservative and revisionist, beatific and brutal, methodical and impulsive, manipulative and fragile. Vladimir Putin is no more than the sum of his parts: the belief in a singular, universal, status and purpose; devotion to Orthodox Christianity; and, finally, in autocracy. In that light, Russia rises above any East-West dichotomy, such is its unparalleled Asian scale. It wards off western yardsticks of individualism and liberalism, which are no more than a source of immorality, as heir to a solid cultural legacy that must remain as foundation to the greatness of the state. Putin's nationalism and melodrama are structural vectors of his plays, stemming from this uninterrupted line of humiliations that begin with the crumbling of the Soviet Union and branch out into Russian liberalization following the American model, NATO's and the EU’s eastward expansion, and attempts to autonomize the European energy market, something unacceptable for one who would cultivate the fervour of a proud and majestic Mother Russia.

Putin joined the KGB in 1975 and built the near-entirety of his career in Dresden, East Germany, where he worked closely with Stasi to recruit local informers. He brought back the terminology employed by Leninist political police (the Chekists) and became a devotee of Yuri Andropov, the longest-serving leader of the KGB. Two factors can explain that. The first is a structural component of the State that bridges the Soviet Union and the Russian Federation: a coterie of bureaucrats and espionage operatives acting on the political and military plane and sustain continuity for the Kremlin court. Some say this fortified wall around the regime includes over three million Russians, the siloviki. Given how competitive the chain of command has proven, the "wall” is also perceived as the best place to move up in the ranks.

The second can best be exemplified by Andropov, the man who reinvigorated an understanding of the KGB as a natural model for all faithful servants of Mother Russia and her imperial shadow. For Putin, Andropov was a change-maker, a charismatic leader, a relentless bloodhound sniffing out traitors, unaccepting of dissidence or democratic leanings, he who had witnessed the dangers of democracy in Budapest when he served there as ambassador in 1956, and then the Prague Spring, when he led the Soviet Union's ruthless response. Andropov followed Brezhnev as leader of the Communist Party and the Union, but his death a mere fifteen months into the new position added new layers to the Andropov myth: for many, including Putin, he was gone all too soon. One had to extend that legacy and his example took root in the post-Soviet state, for which Putin didn't have to invent anything. All he had to do was adapt concepts to keep pace with current standards of scrutiny for political power. In 1999, Ieltsin appointed Putin head of the cabinet. When the presidency fell into ruin and Ieltsin's health collapsed, the baton was handed rather hermetically: Ieltsin abdicated on the last night of the year and Putin was crowned his successor.

Source: The Guardian

This meteoric rise to the top in post-Soviet Russia proceeded along two paths. One, the experience accrued in St. Petersburg, be it learning politics, or controlling financial resources, the latter earning Putin a few accusations of undue appropriation. His dominating stance, and his grip on a bevy of government properties in and out of Russia gave him access to resources and managerial control, turning him into an object of fear in the forest of clans that makes up the Muscovite power system where Putin had been an outsider. To make it in the capital, Putin needed more cards up his sleeve than everybody else put together. Deploying his trump cards, coupled with access to information on Ieltsin's court, made of Putin the most powerful of spies on the bench.

The other fork in his path was repudiating Ieltsin. Putin had always been more of a self-made man within the State apparatus than a protégé of the one Russian in whom the West had put the most stock. Thus he somewhat came to manifest the idea of the "new Russian,” someone outside the State lineage who could discreetly travel the halls of power maintained by a hierarchy dealing with a post-imperial hungover. All Putin needed to do was turn an apotheotic description into national charisma and, to that end, he played up domestic insecurity as a threat to territorial integrity (think Chechen terrorism), and built up a phantasmal enemy outside Russia's borders, embodied in the Western institutions that encroached upon the member-states of the Warsaw Pact.

But when you think about it, what did define the Ieltsin years that Putin paints so dramatically? First of all, the notion of moral humiliation at the West's feet. The collapse of the Soviet Union, which Putin described as "the twentieth century’s greatest geopolitical catastrophe”, was not merely a geographic withdrawal but also the abdication of a system of government. Swift embrace of the "Washington consensus” proved disastrous for an economy best termed ‘unready’, leading to a crushing financial crisis in the mid-1990s. At the time, with the utter failure of economic liberalization and a depleted treasury, the country was paralyzed, bleeding money, and society lived on the verge of serious conflict. The price of oil had come down and the Asian financial crisis cut demand for Russia's energy exports. NATO's eastward additions (1999 and 2004) had exposed the precarious nature of Russian moves: without internal order, economic growth, a modernized military and a renewed push for centring the Kremlin as a bastion of national pride, Moscow would prove unable to check the dynamics of America's unipolar moment. Not only did Russia's command of history seem to have ended, another story was now penned by a single author: Washington. Putin would not accept a role as steward of national humiliation.

Secondly, rampant disorder. No feeling is more strongly rooted in the Russian heart than wanting protection from a strong, paternalistic government, equitable if at all possible, but always a pillar of territorial unity and scale, a guardian of Russian history and bulwark of her anthropological exceptionalism. Putin is this: a representative of collective will, manipulating its fears and anxieties. He provides Russians with order when he disciplines the economy and captures fast-rising oligarchs. He restores their hope when he revisits a past many deem glorious, bringing back the Soviet anthem and promoting major plans of investment in health, education, infrastructure, agriculture, or welfare & support for mothers and seniors. Putin offers protection when he defeats separatist militants in Chechnya, Ingushetia and Dagestan. He clenches an iron fist when he acts ruthlessly toward terrorist attacks in the Moscow theatre, the school at Beslan or arrests "black widows” who blow themselves up in the capital's underground. Russians, who already found consolation in Mother Russia's bosom, now have another watchful parent.

Putin was elected and re-elected; he walked away but then came back "for a free, prosperous, strong, civilized, prideful Russia.” To that end, he needed to raise oil and gas prices in order to fill public coffers and bring buyer countries to heel. Economic growth allowed him to rebuild some of his obsolete war machine and then tell Washington that 30 million ethnic Russians living in his general neighbourhood are under Moscow's protection. That claim covers territory from Belarus to Ukraine, Moldova to Georgia, Estonia to Latvia, and all the way to Kazakhstan.

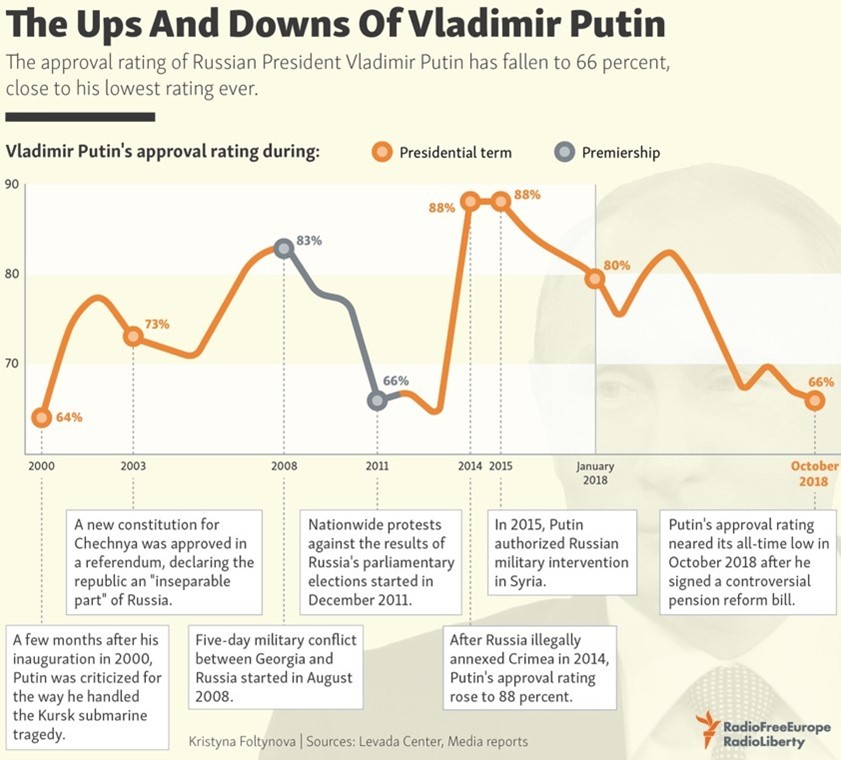

The announcement that History was dead has been greatly exaggerated. Ieltsinian condescension had given way to a Putinian circling of the wagons. Outcry about NATO's expansion followed. An axis of understanding with Paris and Berlin was sought to check US unilateralism in Iraq. Georgia was treated intransigently. The fall of Lehman Brothers provoked some mirth. Every now and again Russia turned off their gas tap so Ukraine would do without. The Kremlin also advanced a customs union with Belarus and Kazakhstan, instituted aggressive state capitalism, promoted a warlike yet level-headed picture of the President, and went about upholding its interests in the Middle East and shaping the US through Syria's civil war. About to turn 70, Putin still wants to be the Hercules that keeps superpowers at bay, the cornerstone of internal unity, the geopolitical strategist that defends Russian minorities in Europe, the lord of Great Russia between unstoppable yet strategically-aligned China, Europe, which tries to decide on the best geopolitical cards to play, and the United States, now pulling out of some places while rethinking others. Annexing the Crimea and sustaining a conflict in the Ukrainian Donbas since 2014 shouldn't have surprised anyone who'd been paying a modicum of attention. 80% approval ratings immediately after annexation (not unlike poll numbers after the war in Georgia) only reinforce this axiom: the bear's breath abroad sharpens its claws at home.

It is precisely when things look shaky at home that the worst intentions move Russia's designs beyond her borders. In October 2021, approval ratings polled at their lowest since 2017 (53%), demography was in decline, the economy stalled, structural dependence on hydrocarbons barred the country from her future, the wish to emigrate rose among the young, vaccination numbers were low for a vaccine-producing country, demonstrations in major cities showed through the cracks in Putinist hegemony, and the cost of living exacerbated inequalities. Freedom of the press and political opposition were still quashed if not eliminated outright, and Russia's neighbours flirted with democratic tendencies — namely in the vast Belarus, in Ukraine, the power & pipeline conduit to the EU, and oil-rich Kazakhstan — all these threats to authoritarian fellowship that would rule over an ideologically homogeneous, Kremlin-led space. It is the construction of this Eurasian union that will turn Russia into a powerful counterpoint to Beijing’s and Washington’s power. Failing at this point will deliver nothing but a continued illusion of global power. And normally, only threatening other countries (especially when you’re a nuclear power) lets you project the illusion that you have a consistent power base. Such continued sleight-of-hand makes Putin a fine strategist and deft deluder on the international political stage.

Disclaimer: Bernardo Pires de Lima, research fellow with the Portuguese Institute of International Relations (Instituto Português de Relações Internacionais) at Nova University of Lisbon.

The views, thoughts and opinions expressed herein belong solely to the author and do not reflect the official positions or policies of, or obligate, any institution, organization or committee he may be affiliated with.

Bernardo Pires de Lima was born in Lisbon in 1979. He is a research fellow at the Instituto Português de Relações Internacionais (Portuguese Institute for International Relations) within Nova University of Lisbon, international policy analyst at Portuguese TV network RTP and radio station Antena 1, political consultant to the President of the Portuguese Republic, chairman of the Curators Council of the Fundação Luso-Americana para o Desenvolvimento (Luso-American Development Foundation), and an author, having published, among other titles, A Síria em Pedaços, Putinlândia, Portugal e o Atlântico, O Lado B da Europa, and Portugal na Era dos Homens Fortes. He has been a visiting fellow at the Center for Transatlantic Relations at Johns Hopkins University in Washington DC, associate researcher at the Portuguese National Defence Institute, columnist for newspaper Diário de Notícias and a commentator at TV network TVI. Between 2017 and 2020, he led the political risk and foresight practice at FIRMA, a wholly Portuguese investment consultancy. He's lived in Italy, Germany and the US, but he keeps coming back to Portugal.