Global Risk Perspectives - Monthly insights on geopolitics, trade & climate

Back to articlesBernardo Pires de Lima

30.06.2022

Seven grand effects of great powers competition

What I’ll try to bring you is a mix of what I have been doing for almost 20 years: interpreting facts, analyzing trends, questioning narratives, raising risks, helping decision-makers. Therefore, my suggestion today is that we look at the seven grand effects of great powers competition, a framework that I think started to define the post-2008 years and has tremendous accuracy for the present context, and, I believe, will shape international relations in the coming years, with great impact on the business environment and consumers’ habits.

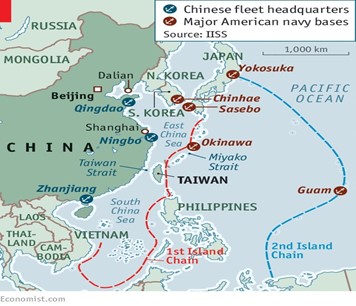

I called the first effect war as a tool for strategic disputes. Not because the use of force has been absent from international politics – actually, it has defined it for centuries – but because now great powers have showed the will to confront each other using military capabilities. The Russian invasion of Ukraine poses a direct threat to NATO countries of an unprecedented nature, and the border that separates the two blocks from mutual confrontation has never been so thin. So, we are moving from a post-Cold War period of mutual accommodation among great powers, to a new phase where mutual military confrontation is on the table. Now, imagine if we have to deal, simultaneously, with a war in Ukraine and a war in Taiwan, with Russia, China and the United States directly involved. This changes everything, from the stability of international order to cooperation for global solutions, to business and economic certainty.

The second effect is cyberwarfare as another level of external intervention. From non-state actors to actors connected to some states, the fact is that cyberattacks have increased over the past years, damaging companies, banks and institutions, but also influencing election results and the democratic atmosphere. In a time of war, lockdowns and disinformation, cybersecurity has never been so relevant to our collective future. And when I say collective, I mean the private and public sectors. But if regulation needs cooperation among states, it also requires the participation of big technological companies across the board. That is still the challenge ahead with a lack of cooperation among stakeholders, which raises the global risk.

The third effect is the clash between democracies and autocracies. Since 2020, and for the first time in the 21st century, the world has more autocratic regimes than democracies. This has at least three consequences: 1) These two parallel systems tend to reduce the level of engagement between them; 2) Autocracies now have more leverage to dispute the merits of democracies and market economies; 3) Democracies now host relevant nationalistic movements and parties that want to roll back liberties, pluralism and international cooperation. These are three consequences that jeopardize the context in which vigorous business operates, creating anxieties in open societies, uncertainty among consumers and strong internal divisions among people.

Bernardo Pires de Lima was born in Lisbon in 1979. He is a research fellow at the Instituto Português de Relações Internacionais (Portuguese Institute for International Relations) within Nova University of Lisbon, international policy analyst at Portuguese TV network RTP and radio station Antena 1, political consultant to the President of the Portuguese Republic, chairman of the Curators Council of the Fundação Luso-Americana para o Desenvolvimento (Luso-American Development Foundation), and an author, having published, among other titles, A Síria em Pedaços, Putinlândia, Portugal e o Atlântico, O Lado B da Europa, and Portugal na Era dos Homens Fortes. He has been a visiting fellow at the Center for Transatlantic Relations at Johns Hopkins University in Washington DC, associate researcher at the Portuguese National Defence Institute, columnist for newspaper Diário de Notícias and a commentator at TV network TVI. Between 2017 and 2020, he led the political risk and foresight practice at FIRMA, a wholly Portuguese investment consultancy. He's lived in Italy, Germany and the US, but he keeps coming back to Portugal.

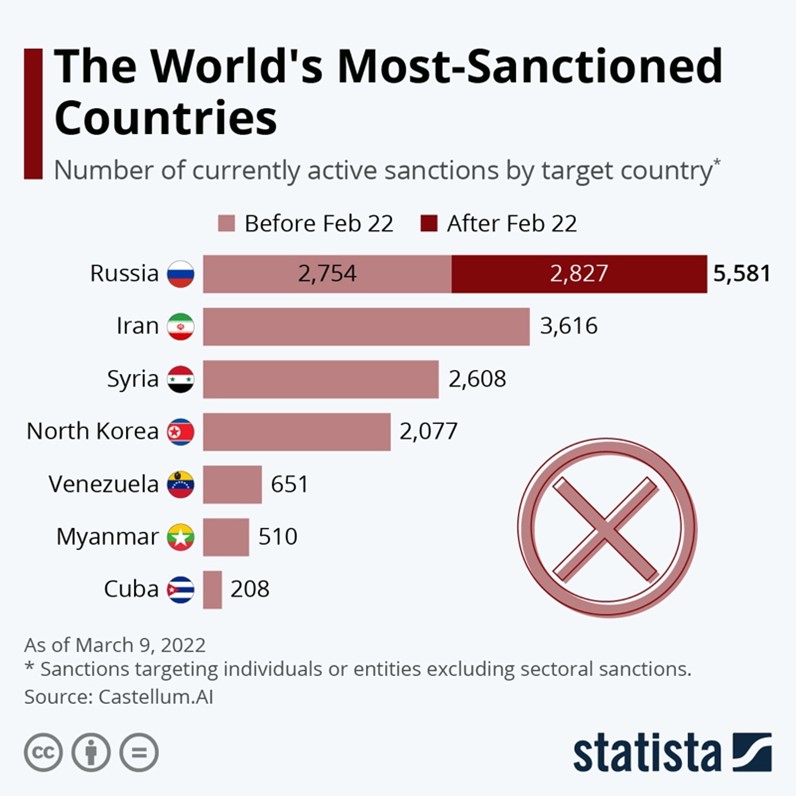

The fourth effect looks at sanctions as part of a decoupling process between industrial economies. We are all aware of the historical fact that sanctions alone won’t solve a conflict. We also know that the current stages of Russian sanctions have not yet achieved their maximum scope. Although we can conclude two things: 1) the west – states and organizations – has been fast to assume that maximum damage must be inflicted on a major power like Russia, until it defaults; 2) the west is owning the collateral risk of cutting its economic, energy and political ties with Russia. This autonomic movement from Europe formally represents the end of an era where economic interdependency has been the guarantee of mutual respect and political engagement between nations. But it also opens a new phase where new big investments will be allocated (energy, infrastructures, defense, technology, industry), fostering new opportunities for the insurance sector as well.

The fifth effect defines an existential threat to multilateral organizations. They are permanently under stress tests, but we recently saw the level of animosity towards the World Health Organization during the pandemic, and the level of crystallization of the United Nations Security Council during the war in Ukraine. On the other hand, NATO and the European Union have shown interesting and surprising levels of cohesion, answering quite well to the challenges posed by Russia. Soon we will witness the creation of a multilateral trade agreement in Southeast Asia, led by the United States, in the coming months, to counteract China’s influence and the economic disruptions it has been posing to the world. So, some organizations are dealing better than others with great power competition. But keep this in mind: if unilateralism prevails, defeating multilateralism, the business environment will also suffer.

The sixth effect identifies long-term disruptions on trade, supply chains, energy and food security. We are all familiar with the tremendous impacts on the global economy, inflation, energy transition, the semiconductor crisis, consumption access, and companies’ normal processes. These disruptive effects linked the pandemic to the war, a long path of global transformations that implied everyone to adapt: citizens, private companies, institutions and organizations. This adaption has had tremendous costs for all of them, and the scenario won’t improve in the foreseeable future. What we can assume is that 1) we will not normalize the global economy until the pandemic is under control, and rigorous lockdowns abandoned, especially in China; 2) we will not rein in the energy and food security effects and the inflation they generate until the war in Ukraine is over, and some kind of political settlement is achieved. And these two steps are still difficult to achieve in the short term.

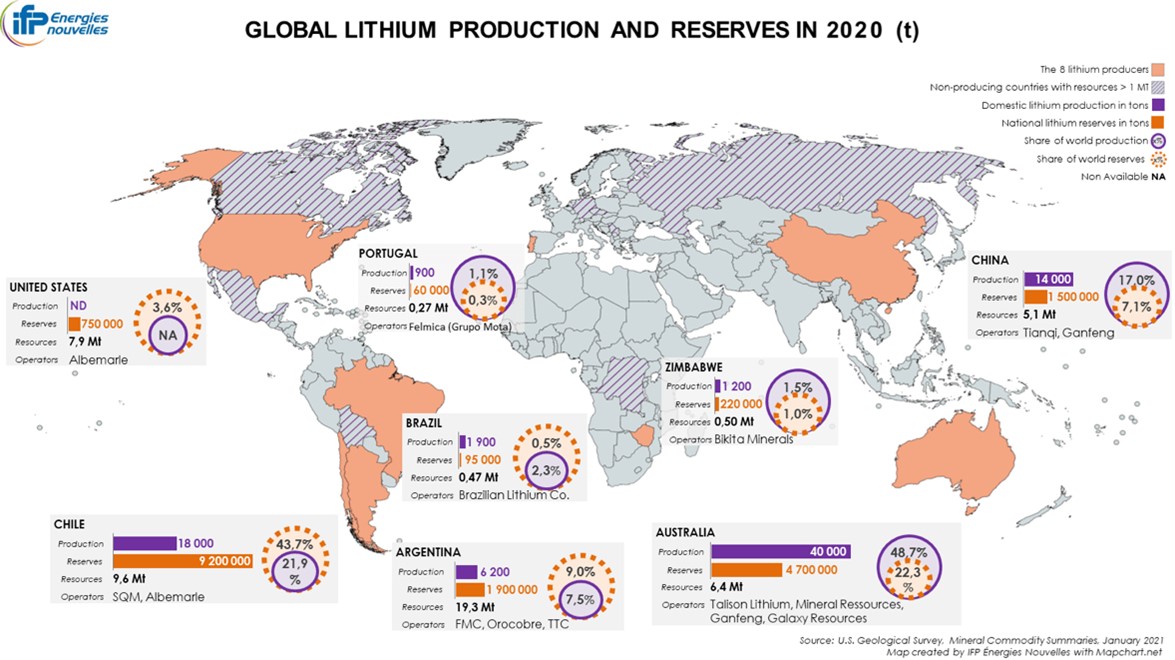

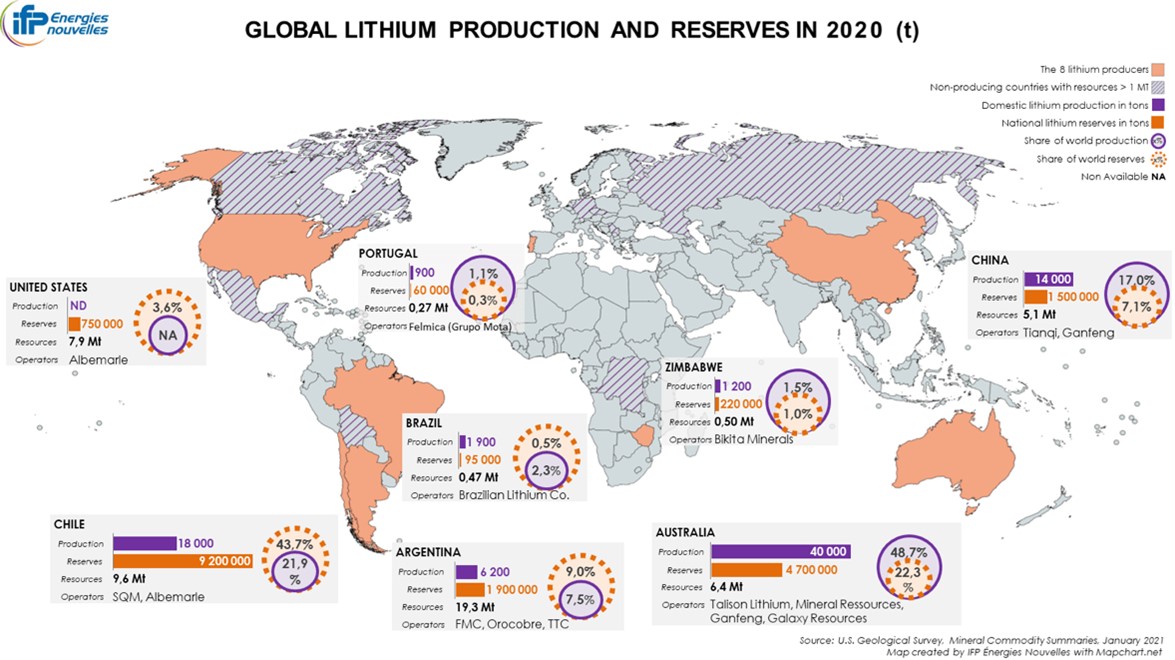

Finally, the seventh effect looks to natural resource extraction for a technological race. Although 80% of the world’s oceans remain unmapped and unexplored – which raises the opportunities for mineral extraction – we have been witnessing the increased importance of new mineral mainland discoveries as part of the technological value chain. I’m talking about lithium, rare earths, cobalt, nickel, copper, zinc, which gives great advantage to countries like China, Australia, United States, Nigeria, Chile, Argentina or Indonesia. Critical raw materials are already at the core of global economy, impacting the environment, and accelerating the extraction process to supply technological competition, a dynamic that is also shaping global power balance. The way this topic is developing will define the level of regulation needed, new climate agreements and perhaps new approaches from the private sector.

Disclaimer: Bernardo Pires de Lima, research fellow with the Portuguese Institute of International Relations (Instituto Português de Relações Internacionais) at Nova University of Lisbon.

The views, thoughts and opinions expressed herein belong solely to the author and do not reflect the official positions or policies of, or obligate, any institution, organization or committee he may be affiliated with.

Bernardo Pires de Lima was born in Lisbon in 1979. He is a research fellow at the Instituto Português de Relações Internacionais (Portuguese Institute for International Relations) within Nova University of Lisbon, international policy analyst at Portuguese TV network RTP and radio station Antena 1, political consultant to the President of the Portuguese Republic, chairman of the Curators Council of the Fundação Luso-Americana para o Desenvolvimento (Luso-American Development Foundation), and an author, having published, among other titles, A Síria em Pedaços, Putinlândia, Portugal e o Atlântico, O Lado B da Europa, and Portugal na Era dos Homens Fortes. He has been a visiting fellow at the Center for Transatlantic Relations at Johns Hopkins University in Washington DC, associate researcher at the Portuguese National Defence Institute, columnist for newspaper Diário de Notícias and a commentator at TV network TVI. Between 2017 and 2020, he led the political risk and foresight practice at FIRMA, a wholly Portuguese investment consultancy. He's lived in Italy, Germany and the US, but he keeps coming back to Portugal.