Global Risk Perspectives - Monthly insights on geopolitics, trade & climate

Back to articlesBernardo Pires de Lima

29.11.2021

The geopolitics of energy, layer by layer

Maybe the most fascinating exercise one can do when analysing international politics is attempting to peel off the layers around events often perceived exclusively from an obvious standpoint. I’ll give you three recent examples, all of them in some way connected with the inflationary pricing of raw material and energy that we’re witnessing.

The first related to the coup in Guinea-Conakry in early September, which drove the price of aluminium through the roof, bringing it to numbers that approach those of the past decade. The country is not only the second leading producer of bauxite in the world, behind Australia, but also represents 25% of bauxite exports. To give you a notion of how crucial this value chain is, 55% of all bauxite purchased by China originates from Guinea-Conakry. It's used for components in the auto industry, and technological applications that make the Chinese economy one of the most vigorous and competitive in the world. All it took was a warning of disruption to international supply chains, caused by the coup, for the impact to rise beyond the local level and become another upsetting factor in the complex puzzle of industrial and commercial globalization.

The second example sheds new light on the matter of separatism in the Western Sahara. The opposition between Morocco and Algeria, once regarded as another frozen conflict on the world stage, involving security and identity concerns, and a 30-year ceasefire that came crumbling down in late 2020, gave rise to new tensions when the US, Trump still being president, recognized Moroccan sovereignty over the territory, as a response to normalized diplomatic relations between Morocco and Israel. Subsequently, Algeria severed its diplomatic ties with Rabat and threatened to close off its airspace to Moroccan planes; furthermore it pondered shutting off the natural gas pipeline that runs through Morocco and into Spain, which also supplies Portugal.

The third example brings out some interesting shades around the systemically tense relationship between the US and China. For years now we’ve been following trade wars, sanctions and counter-sanctions, the latent danger of Taiwan's situation, naval manoeuvres on the South China Sea, but we missed the recent agreement on the supply of natural gas from Louisiana between Venture Global and the state-run Chinese corporations Sinopec and Unipec. With this move, China doubles its annual gas imports from the US and the US takes another step towards leadership in world exports, at a time when the US already is the leading producer. This dynamic not only contradicts the hyperbolic perception that America finds itself in inexorable decline but also that Beijing and Washington can't back out of an impending head-on collision, as some of the effects of the current energy crisis would lead you to believe.

Contextual costs

Economic recovery, with its Asian epicentre, in a context of post-pandemic relief, has led energy demand to spike, especially for natural gas, a preferred resource for economies looking to decarbonize and electrify, where the weight of renewables has yet to achieve significance. The absence of supply to meet demand levels, coupled with disrupted supply chains worldwide, delays in pipeline maintenance and power-maxing moves by some producers, have led to a fivefold increase of gas prices since April 2021.

On-and-off lockdowns, shortages of raw material and semiconductor chips, steep price hikes on essential materials (steel, aluminium, copper, wood, paper), energy costs (oil, gas, electricity), and shipping freight, as well as bottlenecks in worldwide value chains, logistic disruption, accelerating post-pandemic demand, and political decisions to maintain tax burdens on some of these essential products, are asphyxiating companies, industries and families everywhere. Faced with that Juncture, China's Xi Jinping recently signed a decree that will allow the functioning of 73 new coal mines, jeopardizing environmental plans and international agreements. Europe, which relies on imports for 89% of the gas it consumes (Russia supplying 43%), with an industrial deficit and significant reliance on Asian logistics, presents greater vulnerabilities.

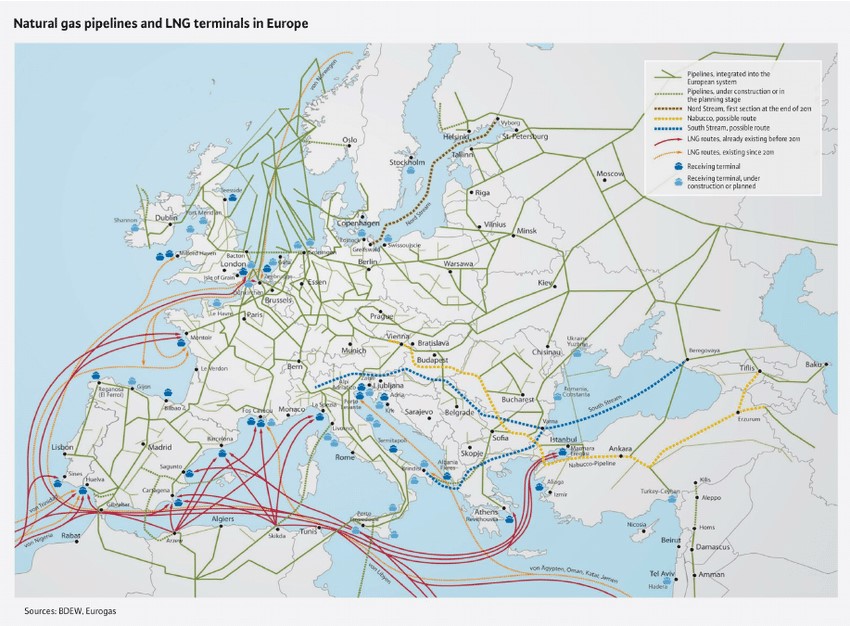

Factors determining prices in Europe over the coming months will, on the demand side, arise from the rigors of winter. On the supply side, Gazprom has bounced back and, at the same time, cut Ukraine off and diverted its supply to the south, via TurkStream2, through Turkey. This pressures Nord Stream 2 to begin commercial operations when Germany is establishing its new cabinet and clearly constitutes a warning to Berlin on its partisan proclivities to backtrack, and cause for concern in the strained relationship with Kiev. This will all bring structural financial impact. Let’s also note that gas production in the Netherlands (Groningen) will stop in 2022, and that may contribute to price hikes if alternatives haven't come up by then.

In the mid to long-term, climate policies in developed countries, especially in the EU, should lead to disinvestment in fossil fuel and more investment in renewable energy. As that transformation unfolds, prices may exhibit additional volatility depending on the pace of investment in continental interconnections. Futures markets signal that prices should slow down from summer 2022. TTF gas delivery contracts in March 2022 are priced at €84,5/MWh, but will go down to €45,4 on Q2 2022. The following autumn, on Q4 2022, the price will be €43,4/MWh. This indicates that markets expect challenges in supply in demand, whether economic or political, will have found resolution by then. However, this does not conceal Europe's structural vulnerabilities beyond that time window.

Pressure on many fronts

In 2020, 80% of gas pricing in Europe arose from market competition and only 20% was indexed to oil valuation, as already happens in the US, but not in Asian countries. If, on the one hand, this allows European countries greater flexibility, on the other hand, it exposes us much more to the ups and downs of international markets. The last European winter was long and severe. The pace of gas depletion was exacerbated by poor output from Norway and the UK, but also Qatar and Iran, partly due to obstacles arising from the COVID-19 pandemic, but also from unstable relationships in the Middle East; discontinued supply of Russian gas; and the fact that renewable sources exposed their limitations, be it lack of wind or limited long-term storage capabilities, which affected exports. This changes expectations as to how these sources will work as alternatives to fossil fuel at the pace many would desire.

Once again it seems increasingly relevant to discuss strategic autonomy including energy, the indispensable formation of a common energy market, which for now lacks infrastructure and connection, diversified sources and vendors, more sustainable and competitive re-industrialisation, with better oversight and control of logistics, and also default scenarios for environmental goals now that we face the need to maintain consumption of fossil fuels (mostly coal and oil), limitations on storage and supply lines for renewable energies, and the temptation some countries might feel to postpone the phasing out of nuclear power. Which means price fluctuation may be inherent to this juncture but the broader impacts to European debate are absolutely structural and inextricable from the Union's future; and Portugal may play a more proactive role in helping define those impacts.

Beyond the conversation around Nord Stream 2, which entails permanent political tension among Russia, the US, Germany, Ukraine and Poland, we might want to take a look at other latitudes, with staggered impacts on gas supply in European markets, on pricing, on electrifying economies and ensuring sustainable and secure supply.

Let us begin with Portugal, the country with the smallest gas reserves available in the EU (49%; EU average, 75%). We are highly reliant on imports from Nigeria, whose internal security is hardly commendable, although supply from the US and Russia has been increasing over the first half of 2021 (according to the latest report from the Directorate-general for Energy and Geology), which made up for cut-offs from Algeria, even though Algerian-supplied gas came cheaper. If tensions with Morocco persist and the contracts that ensure this country keeps a lane into the Iberian Peninsula are broken, throttling gas supply, Algeria may become another disruptive factor for the energy market in the EU and in Portugal.

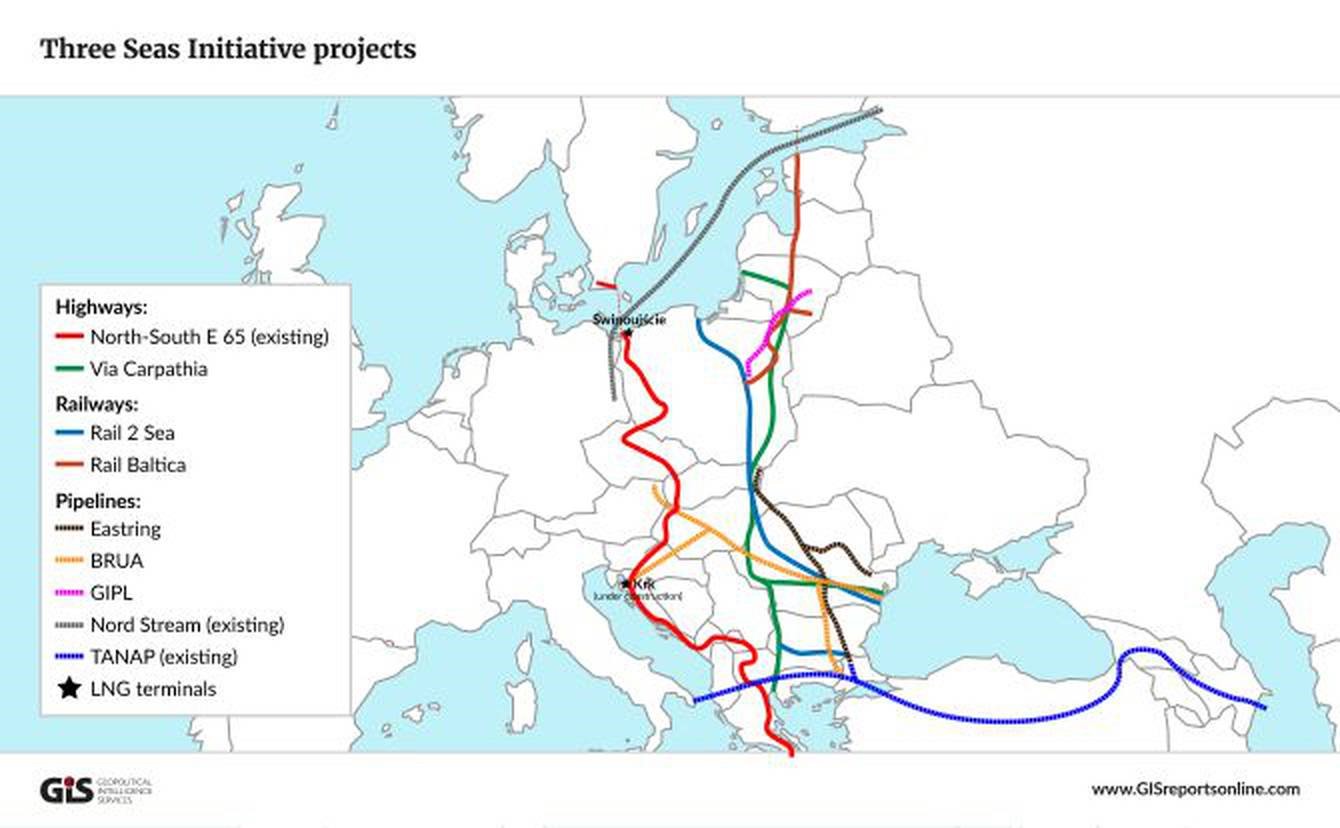

Let us now turn our attention to Portugal's role in Trans-Atlantic relationships. The US-to-Europe pipeline for Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) can come in through Sines, one of the most important European terminals, geographically closest to the US. However, without pushing through much-needed connections in Central Europe (via Pyrenees and the Gulf of Biscay) we will hinder our role in the Trans-Atlantic conversation on energy; nor shall we leverage our rule as an Atlantic-European energy hub. It is fair to remind our readers that the US is the world's leading oil and gas producer, self-sufficient regarding consumption, and that their preferential access points for LNG right now are in Poland and Lithuania.

When Nord Stream 2 begins operations it will secure Russia's strategic position in the European energy and politics framework. Russia's gas lines already give it prominence across geographies (41% via Nord Stream 1 on the Baltic Sea, 29% via Belarus, 22% via Ukraine, and 8% via Turkey and then through the Balkans). This being a potential pome of contention for SPD, Green Party and FDP in Germany, it did not however cause any kind of U-turn in the agreement they recently made public.

Another relevant topic in Europe's energy debate is the Three Seas Initiative, which gathers 12 EU countries for an infrastructure project that covers the Baltic, the Adriatic, and the Black Seas, to diversify sources, vendors, and bring in other transit countries than the usual group. The initiative got an initial boost from Croatia and Poland and garnered bipartisan interest in the US, whose administration has committed to funding a development investment fund. It gives Central and Eastern Europe more political clout, seeks to mitigate Russian influence and bolster American influence and, above all, bypass the unilateralism inherent in many German choices, Germany staying out of the initiative. This matters to Portugal if we are to operate as an entryway for supply to the rest of Europe which, once again, means we need to move forward with our connections to Spain and France.

The Eastern Mediterranean has provided a stage for increasing policy and maritime disputes over the past years, exacerbating historical territorial tension, which once more flare up motivated by new data on its untapped energy potential. Turkey, Greece, Cyprus, Israel, Egypt, Syria and Lebanon are all potential beneficiaries of gas deposits estimated at 76 years’ worth of joint consumption by all EU countries. Competition has given rise to a number of diplomatic overtures among countries in the region, with American and Russian companies entering the playing field, but we’re also looking at the ingredients to brew more conflict in Europe's vicinity. New producers and supply routes entering the scene in the mid-term must also be taken into account in the debate on energy in Europe.

Finally, one should assign relevance to the Arctic, where 30% of all the untapped gas in the world may lie. Heat rising on the poles now permits new kinds of joint exploration for major companies, as well as the time extension of much faster shipping lanes between Asian and Northern European ports, shaving 12 days’ navigation off current courses, which impacts costs and bypasses piracy on the Indian Ocean. If ice cap melting and energy competition accelerate in the Arctic, lanes including the Suez may in time lose relevance and therefore so will the Mediterranean-Atlantic connection, which matters to Portuguese trade interests. The ongoing debate on climate change is, for this reason also, of primary relevance to Portugal's national interest.

Disclaimer: Bernardo Pires de Lima, research fellow with the Portuguese Institute of International Relations (Instituto Português de Relações Internacionais) at Nova University of Lisbon.

The views, thoughts and opinions expressed herein belong solely to the author and do not reflect the official positions or policies of, or obligate, any institution, organization or committee he may be affiliated with.

Bernardo Pires de Lima was born in Lisbon in 1979. He is a research fellow at the Instituto Português de Relações Internacionais (Portuguese Institute for International Relations) within Nova University of Lisbon, international policy analyst at Portuguese TV network RTP and radio station Antena 1, political consultant to the President of the Portuguese Republic, chairman of the Curators Council of the Fundação Luso-Americana para o Desenvolvimento (Luso-American Development Foundation), and an author, having published, among other titles, A Síria em Pedaços, Putinlândia, Portugal e o Atlântico, O Lado B da Europa, and Portugal na Era dos Homens Fortes. He has been a visiting fellow at the Center for Transatlantic Relations at Johns Hopkins University in Washington DC, associate researcher at the Portuguese National Defence Institute, columnist for newspaper Diário de Notícias and a commentator at TV network TVI. Between 2017 and 2020, he led the political risk and foresight practice at FIRMA, a wholly Portuguese investment consultancy. He's lived in Italy, Germany and the US, but he keeps coming back to Portugal.