Global Risk Perspectives - Monthly insights on geopolitics, trade & climate

Back to articlesBernardo Pires de Lima

24.01.2022

The Global Challenges of Water Politics

While a part of the world remains focused on the pandemic, another faces the added risk of going without water. I do not speak of conflict on the high seas or disputes over shipping lanes, naval competition or oil and gas extraction. I mean the smaller portion of the world’s water flowing from rivers and river basins, 70% used in agriculture and a cause of existential dread to many peoples in Africa, the Middle East and South and Central Asia. Let us recall at this point that over 160 countries rely on imported foodstuffs, which means a minority group is feeding most nations. Let’s not forget, either, that according to UN reports 40% of the world’s population is already living with "water scarcity” and other studies point to forced migration stemming from that very cause — the displacement of 700 million people or so by 2030.

The ongoing drama is an explosive concoction of factors that potentially damages the relationship between agricultural producers and consumers but also objectively exacerbates tendencies for conflict across variable geographies. We’re looking at prolonged drought, water scarcity, rising ocean levels, shifting borders, increasing food insecurity, rising prices of essential commodities, massive population shifts toward large cities and out-of-control pressure on their resources and services; social revolt, civil war and, as if that were not enough, a global tilt toward nationalism that could undermine what’s left of good diplomatic diligence.

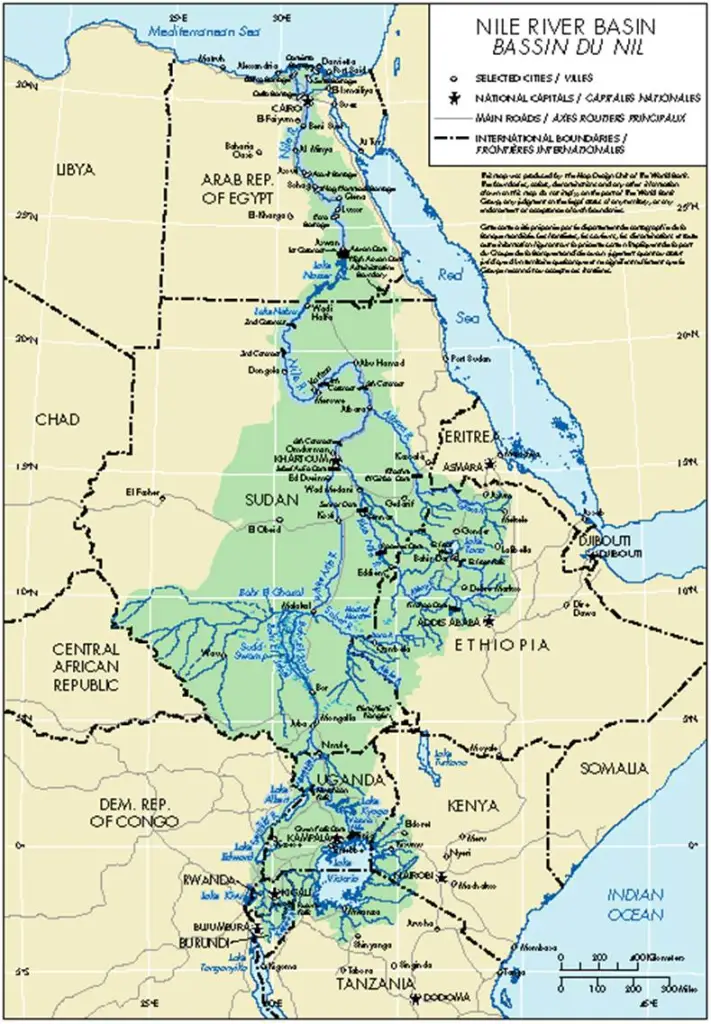

The Nile, Tigris and Euphrates Basins

It is estimated that the Earth will have 8 billion inhabitants by 2025 and that food production will double, forced by demand, and that water will be an indispensable ingredient in that value chain. Over the coming fifteen years, the number of people living in water-scarce areas is expected to grow from a billion to four billion (an estimated 50% of the world’s population) and 60% will live in major urban centres where demand for water greatly strains the available supply — places like Jakarta, Lagos or Beijing.

Just think of the Nile. It cuts across 11 countries plagued by intermittent conflict which feeds into parallel threats (terrorism, piracy, drug trafficking). That does drive home the relevance of our topic today. With its Ethiopian wellspring, it flows out to Egypt, whose agriculture relies on the river for up to 80% of production. Management of the Nile’s levels is vital to 250 million people. Recent construction advances in the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, avowedly the largest in Africa and seventh in the world, which will drive more agricultural production and energetic abundance, has recently motivated Egypt and Sudan to conduct their second joint military exercise in six months. So what’s their accusation? That finishing the dam would cut the flow of water to Egypt by 25% in a mere five years and cut energy output in the Aswan dam by 30%. All this despite the existence of a multilateral regulatory forum and agreements among stakeholders in the basin, which speaks to the fragility of the agreements now in place. This goes some way toward explaining conflagrations in the Horn of Africa.

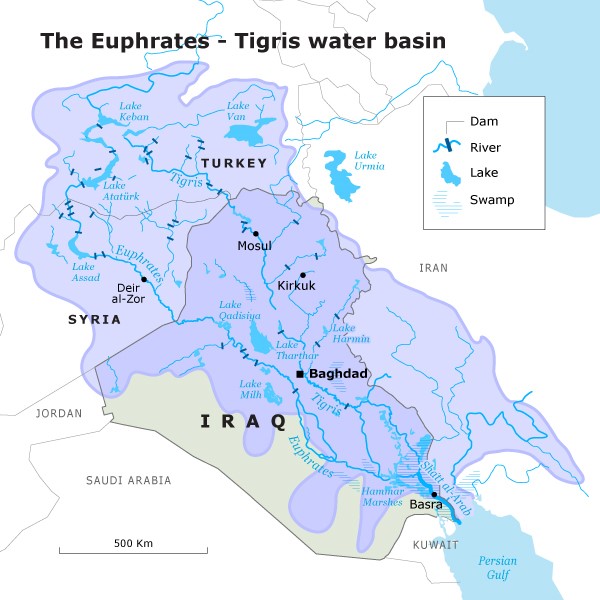

Let us now travel to the northeast. When temperatures reached 50°C across Turkey in 2019, the country decided to accelerate a mega-project in their southeast which encompassed the building of 22 dams and 19 hydro power plants over the next few years. Pushed by the effects of the double combat against climate change and water stress, Turkey’s endeavours translated into less water for Syria and Iraq, opening the way for the salt waters of the Persian Gulf to mingle with the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, killing crops and harming public health. The basins of the two fabled rivers are crucial for Turks, Iraqis, Iranians and Syrians. Any unilateral decision affecting either could have perverse consequences to the precarious stability of each country. Let us briefly recall the intense drought that affected Syria between 2006 and 2011, pushing over 1.5 million people to seek resources, services and employment to its major cities. President Assad reacting by ending a years-long string of subsidies on fuel, agriculture and water extraction, paving the way for regular protest that led to the ongoing civil war. Sometimes, a community’s vulnerability to drought could harm them more than the drought itself.

A parallel drama unfolded when in July 2014 the leader of ISIS, Al-Baghdadi, announced the formation of the caliphate at the al-Nuri mosque in Mosul. Three years later, its destruction at the hands of the very ISIS prompted the Iraqi prime-minister to announce the "liberation” of Mosul. The great northern Iraqi city of "peaceful coexistence” had been officially liberated and yet all but razed to the ground. Few buildings still stood. A humanitarian crisis lay revealed to the world: no water, no power, no work. Over a million people displaced. In the short term, Mosul required an investment of a billion dollars in infrastructure alone. Destroying it from above was the easy part; building back on the ground proved a different challenge.

But why Mosul? The second largest city in Iraq, mostly Sunni in makeup — a plus in a Shi’ite majority country — Mosul was a strategic hub for water management. It possessed the largest dam in Iraq, which also happened to be the fourth largest in the Middle East. No less importantly, it boasted the largest Iraqi oil pipeline, which served Turkey and was located 150km from Syria, allowing for control over two territories where borders are porous, revolutionizing the map of the Middle East drawn over the past half-century and demonstrating how easy it would be to occupy Iraq once American troops had withdrawn. Success in Mosul and the establishment of the caliphate inspired thousands of zealots all over the world, galvanizing jihadi cells in Europe and motivating the entrance of self-appointed terrorists into the Pantheon of Terror: Paris, Brussels, Nice, Berlin, Manchester and London have shown it was so. As an example, controlling the Mosul dam (as an economic asset that could be used to retaliate, should it become necessary to blow it up and so wipe out entire towns) well evinces how strategies of water domination are not exclusive to governments in times of war and peace but employed as a priority by subversive non-state actors capable of upending regional order and extend their ideological dominion over an ample and variable geometry.

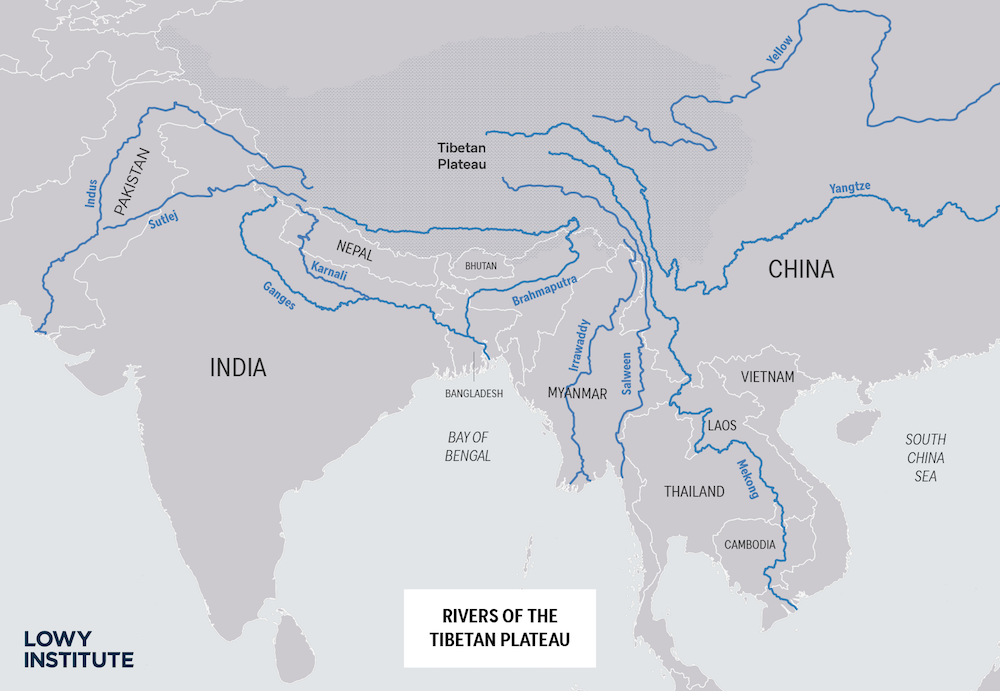

From the Tibetan Plateau to the Mekong Delta

Now let us cast an eye toward competitive Asia. Part of the conflict over Kashmir between Pakistan and India owes to control of the Indus River. Either centred here, or on the five tributaries that flow across both countries, especially the fertile region of Punjab, claims to Kashmir place on the table the use of water flows as a way to choke economies and livelihoods of the people who depend on those rivers, especially the three quarters of the Pakistani population that relies on them. Once again, despite the bilateral treaty in place since 1960, several gaps remain, and interpretations collide. Under a context of ongoing competition, mutual distrust and uncertainty between the two countries, both of them nuclear powers, any mismanagement of water resources can tear open new fronts for conflict — conflict which, truth be told, has never gone away.

Their neighbour, China, has a compelling reason to keep Tibet under its thumb. The main Asian rivers, the Yellow River, Mekong and Yang-Tse (the largest in Asia) flow from Tibet. Eleven countries, from Afghanistan to Vietnam, depend on them. Widespread construction of dams in China is not a product of chance. It stems from their lukewarm participation in 39 agreements that have since 1948 governed basin systems in Asia. Brahma Chellaney raises the alarm in Water: Asia’s New Battleground. This is a serious matter. One need not explain what conflicts in Asia mean to the world’s economy, whether they arise out of water control, rare earth minerals or border disputes, as happens on the South China Sea. Add to that rising sea level as a perverse effect of climate change and the alarm will extend to human and critical infrastructure security in major Asian cities, all of them coastal. Cities like Mumbai, Karachi, Shanghai, Tokyo or Jakarta.

The importance of major rivers in Chinese history has shaped political power, social stability and community feeling. Their basins have always proved vital for agricultural development, trade, and transportation; sustaining imperial dynasties, the Maoist apogee, Deng’s reforms and Xi’s neo-imperialism as they advanced or withdrew along the axis of Chinese development. Today, the roulette of industrial indexes and the course of climate change have impacted new dynamics upon Chinese water politics. Pollution levels are rampant as gargantuan dams rise from the ground. Entire cities are flushed out as ecosystems get flattened, public health gets crushed, hospitals face increasing demand, demographics suffers, social unrest spikes, and all these factors are exacerbated by the 25% reduction in water flow expected by 2050. Without changes to the economic paradigm and political attitudes, internal and regional impacts could be massive. And what of the need to provide for 300 million Chinese who have no access to potable water?

In February 2021, China unilaterally decided to cut the flux of Mekong by 50% with not a word of warning, for three weeks, alleging "equipment maintenance” as a motive. A few months earlier, it had entered a multilateral management agreement with the other countries that rely on the Mekong. Effects played out across Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam, Myanmar and Thailand, who suffered protracted disruptions to transportation, trade and agriculture, affecting hundreds of millions of people. Once again, it does not seem that multilateral water governance agreements are robust enough to shape the political behaviour of countries who see rivers as one of the most significant geopolitical instruments at their disposal to exert their skill and flaunt their power. Although none of this is new, historically speaking, at a juncture like this, combining water stress with climate changes and nationalistic revanchism, it all represents systemic risk to international politics and necessitates close attention.

Disclaimer: Bernardo Pires de Lima, research fellow with the Portuguese Institute of International Relations (Instituto Português de Relações Internacionais) at Nova University of Lisbon.

The views, thoughts and opinions expressed herein belong solely to the author and do not reflect the official positions or policies of, or obligate, any institution, organization or committee he may be affiliated with.

Bernardo Pires de Lima was born in Lisbon in 1979. He is a research fellow at the Instituto Português de Relações Internacionais (Portuguese Institute for International Relations) within Nova University of Lisbon, international policy analyst at Portuguese TV network RTP and radio station Antena 1, political consultant to the President of the Portuguese Republic, chairman of the Curators Council of the Fundação Luso-Americana para o Desenvolvimento (Luso-American Development Foundation), and an author, having published, among other titles, A Síria em Pedaços, Putinlândia, Portugal e o Atlântico, O Lado B da Europa, and Portugal na Era dos Homens Fortes. He has been a visiting fellow at the Center for Transatlantic Relations at Johns Hopkins University in Washington DC, associate researcher at the Portuguese National Defence Institute, columnist for newspaper Diário de Notícias and a commentator at TV network TVI. Between 2017 and 2020, he led the political risk and foresight practice at FIRMA, a wholly Portuguese investment consultancy. He's lived in Italy, Germany and the US, but he keeps coming back to Portugal.