Global Risk Perspectives - Monthly insights on geopolitics, trade & climate

Back to articlesBernardo Pires de Lima

21.09.2021

The Great Wall of China

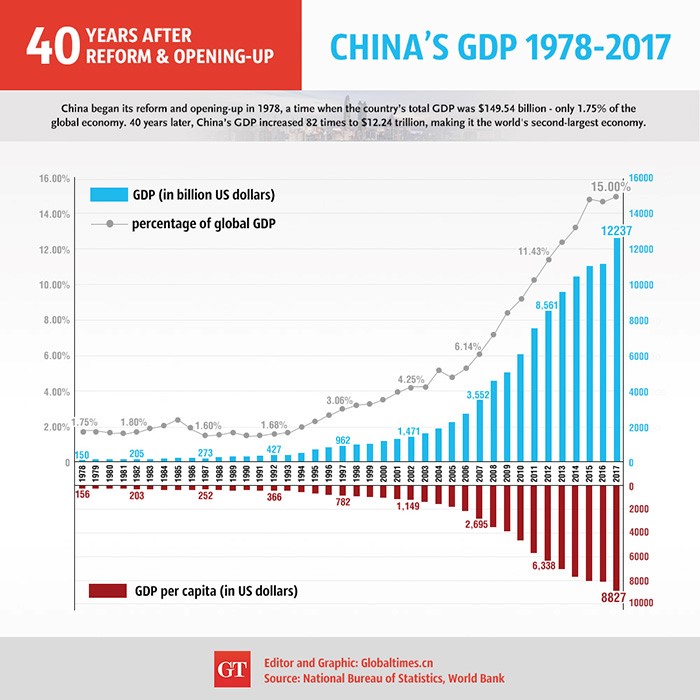

Xi Jinping's China is undergoing its third major transformation of the post-war period. After the long Maoist revolution spread over a continentally unified China and slashed open a million wounds, cutting an ideological swath through the two reigning poles of the Cold War, Deng Xiaoping's reformist opening surfaced a more confident, more deeply integrated, wealthier China. Over 40 years its GDP grew 82-fold, leaping to the summit where major powers keep their perch, making a bold statement as to China's geopolitical affirmation across the Indo-Pacific space. This brings us to the age of Xi Kinping.

Xi is the first chairman without revolutionary pedigree even though he is the soon of a high-ranking official from the generation that pioneered communism, the ‘red princes’. Jinping's father served at one point as vice-premier of the State Council of the People's Republic of China. Although Xi Jinping paid his dues in the Communist Party, where power resides, he was only admitted to the Party on his tenth attempt. He's been in the Party's inner circle since 2007, but he comes for a lineage that displays greater openness to the world outside China, learning from comparative experiences, having spent time in the USA to learn of its progress on fields such as agriculture or technology. His only daughter went to Harvard, embarking on the same path that would take over 3 million Chinese students to American universities over the past decade. The great paradox of the Xi era is that the transformations underway are more imperial and nationalistic in nature than Xi's apparent, tolerant cosmopolitanism might lead one to believe.

That’s the matrix China's great strategic consolidation arises from, with which western and Asian democracies must now contend with.

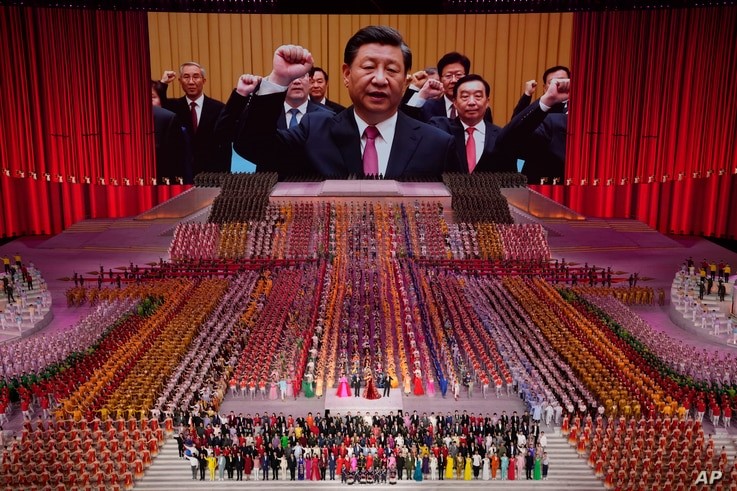

So does the CCP flex muscle

The Chinese Communist Party's (CCP) recent centennial was an illustrative confirmation of Xi Jinping’s nationalism, which has ramped up since he ended the two-term limit for presidents, which will allow him to remain in office indefinitely. All signs point to Xi using the 20th party conference in 2022 to announce his dual role as national chairman and party leader taking after his great inspiration, Mao Zedong. Such absolutism has proved an ineluctable feature of Chinese state apparatus, but also a conditioning factor for corporate business and social conduct.

At present, every Chinese institution, ministry, university or company can become a party branch if it employs thirty or more CCP members. Courts and armed forces systematically report to the party, and so do news agencies or directors of other state media. The military is subordinate to the party, namely to its military committee, led by none other than Xi Jinping. A social credit system has been put in place to reward obedience and punish dissent, resorting to technological scrutiny of citizens’ daily comings and goings. It is no surprise that the party's militant youth wing has become a privileged means of climbing the social ladder. For the first time in its history, the CCP has more members among college graduates and the professions than it does low-skilled factory workers or low-income rural denizens.

Xi Jinping has not only fine-tuned the CCP's power but he has restored nationalism, accommodated by a support cast of contemporary "strongmen” in a number of countries. In addition to getting rid of term limits, which was despite everything else a good feature in the Chinese state apparatus, he has accelerated the comeback of Marxist-Leninist training in schools, dealt ruthlessly with the Islamic minority in Xinjiang, imposed party control over the autonomous administrative regions of Hong Kong and Macau and further tightened the party's grip on corporations. At home he rouses the masses against foreign powers while on international forums he speaks words of appeasement, upholds liberal order, multilateralism and free trade. This two-faced approach plays into the numerous grey areas that modern-day China represents to democracies, especially western ones: more mysterious than it is understood, more tolerated than criticized, more patronizing than demanding.

Totalitarian restoration, combined with external expansion via the Belt and Road initiative, supported by over 140 countries, has been a magical formula for universal ascent, but that global integration has not brought any openness or democratic reform to the regime. On the contrary. The governance model China has to offer, antagonistic to liberty or checks and balances, is now seen by many as a viable alternative by those who would accumulate wealth as despots and grind pluralism into the ground, ignore equitable health distribution and eschew the organization of a politically mature civil society with the will and the means to ensure oversight. With or without the pandemic, given the current, reigning exhaustion, the CCP will face a reckoning of its status and power on the economic plane. In other words, only the relentless pace of economic growth over the past decade can guarantee political stability in China, the perpetuation of the current architecture of power, and external consolidation of its financial, logistic, military and geopolitical capabilities. Despite apparent signs of sustained economic growth, two trends are worth keeping up with: excess leverage in banking and overheating in the financial sector. Add to that the inconsistent quarterly pace of economic recovery.

How long this evolution lasts will also dictate Beijing's capability to continue shaping international politics on the same terms as over the past two decades, funding major regional development and guaranteeing stabilized popular legitimacy for the Communist Party.

Incomprehensible division in the West

No doubt the multiple points of view on China's current power among western and Asian democracies are an endless source of contention. This can hardly be overcome in coming years. The recent NATO summit in Brussels evidenced how China has become a major point of strategic dissonance (and so has Russia), whether the point is defining China’s status or determining what tools must be used to deal with it. Some think of China as a strategic rival, others as an adversary or an enemy, a threat. Others advocate for constructive dialogue and indispensable cooperation channels, along with further integration into major world security decisions.

However, Washington still sets the pace and, rhetorical shifts notwithstanding, Joe Biden firmly maintains his assessment that China’s more interested in domination than coexistence. It is precisely this inflexible stance that sows dissent among allies. However, the Biden administration greatly values their network of allies throughout Europe and the Indo-Pacific area, and wants to strengthen it and bring it to the fore so that the US will retain its decisive, not to say hegemonic, linchpin privileges whenever major strategic decisions are on the table in Tokyo, Berlin, Canberra, London or Seoul.

This is exactly where we stand and it’ll have an impact on key developments this decade, such as 5G, investment agreements, the need for hospital supplies and pharmaceuticals, reaching climate goals, preserving sovereign borders or lawful control of shipping lanes. Xi Jinping rose to power in 2012 but, since then, neither western nor Asian democracies have found a robust, well-structured method to deal with China. Time once again seems to favour the Beijing approach.

Looking for an aggregating strategy

Few may now remember that the early days of the George W. Bush administration were defined by serious military tension with China, which was perceived as the US’s major strategic challenge. If 9/11 moved the needle, it is no mistake to say Beijing never blinked out of Washington’s radar. The Clinton years witnessed post-Cold War democratic expansion and growth of leading international organizations — with China joining the WTO in 2001 after 15 years spent in negotiation. President Obama, pressured by the long engagements in Iraq and Afghanistan, tried, in the time he was allotted, to have his grad strategy include recognition of the role played by regional powers, seeking dialogue with Hu Jintao’s China, Dmitri Medvedev’s China, Lula da Silva's Brazil, Hassan Rouhani’s Iran or prime-minister Manmohan Singh’s India. Despite some setbacks there were a few good multilateral wins, like the monitoring of Iran's nuclear program, bringing it back into the world economy, or the Paris Agreement on climate change, which wouldn't have come to fruition without Beijing or New Delhi getting on board. Donald Trump’s arrival sees the intentional rollback of such multilateral progress and initiates a course of direct belligerence with Beijing. The outcome, as we know, did not strengthen US hegemony or stop China's rise. It placed allies between a rock and a hard place. Attempts to bundle up China with the coronavirus did not help the Republican win the 2020 election either. Joe Biden now endeavours to synthesize earlier presidential approaches.

He has gone for a slight shift in tone without changing strategic focus. It is pretty much a given in Washington that China's the United States’ greatest strategic foil in the 21st century, touching on multiple variables, from the security of Asian allies to trade wars, from clashing ideology and governance models to technological primacy and dominance in space, from the effects of energy transition to renewed industrial competition. What recent months have shown, Joe Biden not having fully course-corrected, is a more reactive United States, less willing to embark on a uniting strategy against China: for democracy, freedom, human rights, alliances, technological and trade regulations, more industrial and strategic autonomy in European and Asian democracies.

At this stage, digital and technological governance look like a priority, and so does the push toward 5G in Europe, as means to bring Europeans and Americans closer and further separate Europeans from the Chinese. It's under this dynamic that we see a focus on breaking up the 17+1 forum which currently congregates several Central and Eastern European countries, plus China. So far, only Lithuania has left. Although this first stage isn't finished, the way forward seems more or less evident if you pay attention to the meetings between US and EU authorities.

Secondly, but no less relevant, is the understanding, on both sides of the pond, that reindustrialization must accelerate, supply chains become autonomous, and reliance on China, brought into stark relief during the pandemic but strikingly evident before then, cut short. That’s instrumental to galvanizing world economies. However, a significant portion of natural resources for energy transition includes rare earth minerals, such as lithium or cobalt, where places like China, Australia and Africa have an advantage over the US or Europe. It is certain, nevertheless, that both Americans and Europeans are more eager to map out their geological resources and keener on exploiting them.

In June, the Biden administration finished reviewing their supply chain strategy, based on the quick downscaling of reliance on China and bolstering regional alliances. Although that may make sense strategically, there’s a small issue called environmental impact, which may put paid to that ambition. Biden, like the UE, derives some legitimacy from plans to combat the climate crisis and advocating more sustainable economic transitions. A U-turn on that could demotivate a part of the electorate and stall the agenda on environmental solutions which planetary health requires.

The third apparent alignment during this first stage illustrates the West’s reactive dynamic. The June meeting of the G7 in the UK signalled that the group would pursue an alternative to China’s Belt and Road Initiative with a 40-trillion USD package that would compete with ongoing investments in Asia, Africa and Europe on commercial, logistics and transportation infrastructure. This B3W, or Build Back Better World, will provide the world with a choice that tends toward good governance and environmental sustainability more than China’s offering, and represents an ambitious tool to unite political wills. However, it’s off to a late start, without any assets on the field of play. It does not anticipate Chinese moves, it reacts. It's not enough.

One way to dispel the international perception of the Biden administration’s posture as reactive and combative would be to create regular bilateral or even trilateral forums with the EU, as well as define a few points of agreement on how to manage globalization that require alignment from Washington and Beijing (climate, nuclear safety and security, technological governance, trade rules). Recent diplomatic meetings show that this is possible and strategically desirable, with a desirable side effect: keeping Beijing and Moscow from deepening their relationship. For that very reason, the creation of a NATO-China Council might serve as a lowest common denominator to resolve disputes among allies, send a clear signal to the Kremlin, and provide the West with better knowledge on the complexities of China’s politics and military power. But I fear that we’re not there yet, not even close.

Disclaimer: Bernardo Pires de Lima, research fellow with the Portuguese Institute of International Relations (Instituto Português de Relações Internacionais) at Nova University of Lisbon.

The views, thoughts and opinions expressed herein belong solely to the author and do not reflect the official positions or policies of, or obligate, any institution, organization or committee he may be affiliated with.

Bernardo Pires de Lima is Political Adviser to the President of the Portuguese Republic. He is also a Research Fellow at the Portuguese Institute of International Relations, IPRI-NOVA, an international politics analyst for the national Portuguese television channel RTP, for radio station Antena 1 and the Portuguese daily Diário de Notícias. He chairs the Luso-American Development Foundation’s (FLAD) Curators Council and has been a Research Fellow at the Johns Hopkins Center for Transatlantic Relations in Washington DC and at the National Defense Institute in Lisbon, Portugal. He has penned eight books on contemporary international politics, the most recent being Portugal na Era dos Homens Fortes: Democracia e Autoritarismo em Tempos de Covid (Portugal in a time of strongmen: Democracy and authoritarianism in a time of Covid), published by Tinta-da- China in September 2020.