Global Risk Perspectives - Monthly insights on geopolitics, trade & climate

Back to articlesBernardo Pires de Lima

18.05.2021

The two major crises of the century

Global trade and geopolitics are historically intertwined. Major civilizations and empires, and later nation-states, tied their territorial ambitions to broader control over shipping lanes and key strategic locations for logistics, setting up defence nodes with varying degrees of permanence. This effort furthered science and brought about technological revolution, spread ideologies, refined diplomatic relationships, led to the signing of treaties, and building cooperation but also caused rifts between states and even continents. Over the past fifty years, this dynamic has taken place under the consolidated watch of international bodies.

In this late-stage globalization, marked by the spread of free trade to new parts of the globe as a consequence of the geopolitical transformation subsequent to the end of the Cold War, which has been accelerated by China’s joining the World Trade Organization (WTO), the EU’s eastward expansion and the rise of the Euro, we’ve witnessed two moments of systemic disruption that are distinct in nature: the financial crisis of 2008-2009 and the 2020-2021 pandemic shock. Considering the first one emerged from accumulated flaws in the financial system and had its epicenter in the USA's real property market, the latter came from a spiral of responses running against the clock to contain a public health drama that turned national economies on their head. Ten years ago we dived headlong into austerity and nowadays we discuss unprecedented stimulus packages.

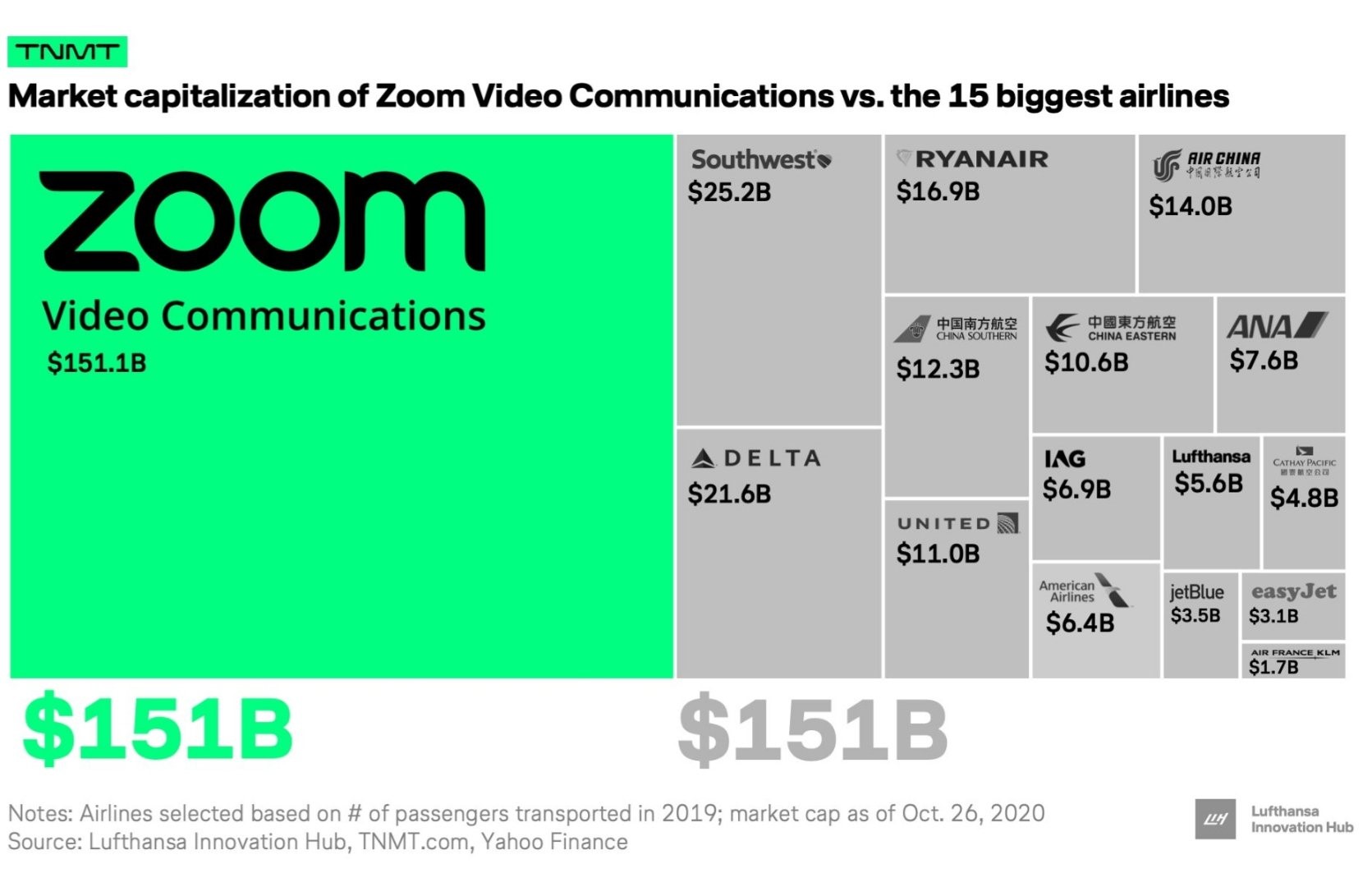

The Great Recession brought about the collapse of the banking system. Countries and financial organizations sought to control and contain the damage to public and private debt and rising unemployment. As for the pandemic shock, the banking system bounced back, adapted, and countries, as well as regional organizations, took up expansive financial policy to build a social safety net that could withstand the damage. The first shock heralded the rise of major global technology businesses (WhatsApp, Uber, Instagram, Slack, Pinterest, Groupon, Square, Venmo, Zoom, Airbnb), which changed the way we consume, socialize, seek funding and engage with the workplace. The second brought a rescaling of such businesses, combined with the notion that it is indispensable to reindustrialize, secure the logistics for essential goods and services, and highlighted government roles in protection of employment, companies and public services.

As for geopolitics, 2008 was the year Russia and China decided to affirm their neo-imperial drives, with the war in Georgia and the apotheotic display of the Olympics, respectively, distinctive manifestations of power that would echo throughout the coming decade and put these countries on a collision course with American hegemony, which had already suffered a blow from the Great Recession. The chips are still mostly where they fell, which proves that shifts in international order can be less sudden that we imagine. Moscow's later aggressive moves in Ukraine and Syria, along with Putin’s entrenchment in the seat of power, were not followed by sustainable economic growth or productive diversification, slowing down recovery from external shock — Russian GDP is comparable to Spanish GDP, which points to a dim near future and forces the Kremlin to smoke-screen its vulnerability by acting like a bully abroad and exalting an obsolete mythology.

In Beijing, Xi Jinping's imperial confidence, starting in 2012, relies on more varied tools of globalization, starting with mega-infrastructure projects throughout Asia Minor, Central Asia, Africa, Europe and Latin America. No less important is the apparently limitless funding, which now feeds into an internal bubble of concerning proportions. Let us not forget, either, China's territorial ambitions on the South China Sea, which puts them at odds with their regional neighbours who can't help but worry about China's exponential Defence expenditure: its budget rose by 400% over a single decade and is now the second largest in the world.

This was the playing field where Washington tried, over the last decade, to find a role for itself after the subprime crisis shook the country to its core. Under Obama, the US sought to accommodate several regional rises to prominence (China, Russia, India, Iran, Turkey, Brazil), with varying responses and outcomes. Under Trump, the US tried to revert all it could and opted for permanent belligerence on trade, security, climate change, diplomacy, energy, migration, and the role of international organizations. The scars left behind by Trump's tenure and the simultaneous outbreak of the pandemic, whose chief effect was to deny Trump a second mandate in 2020, already let us perceive a few trends for the coming years.

Bernardo Pires de Lima is Political Adviser to the President of the Portuguese Republic. He is also a Research Fellow at the Portuguese Institute of International Relations, IPRI-NOVA, an international politics analyst for the national Portuguese television channel RTP, for radio station Antena 1 and the Portuguese daily Diário de Notícias. He chairs the Luso-American Development Foundation’s (FLAD) Curators Council and has been a Research Fellow at the Johns Hopkins Center for Transatlantic Relations in Washington DC and at the National Defense Institute in Lisbon, Portugal. He has penned eight books on contemporary international politics, the most recent being Portugal na Era dos Homens Fortes: Democracia e Autoritarismo em Tempos de Covid (Portugal in a time of strongmen: Democracy and authoritarianism in a time of Covid), published by Tinta-da- China in September 2020.

Disclaimer: Bernardo Pires de Lima, research fellow with the Portuguese Institute of International Relations (Instituto Português de Relações Internacionais) at Nova University of Lisbon.

The views, thoughts and opinions expressed herein belong solely to the author and do not reflect the official positions or policies of, or obligate, any institution, organization or committee he may be affiliated with.