Global Risk Perspectives - Monthly insights on geopolitics, trade & climate

Back to articlesBernardo Pires de Lima

17.12.2021

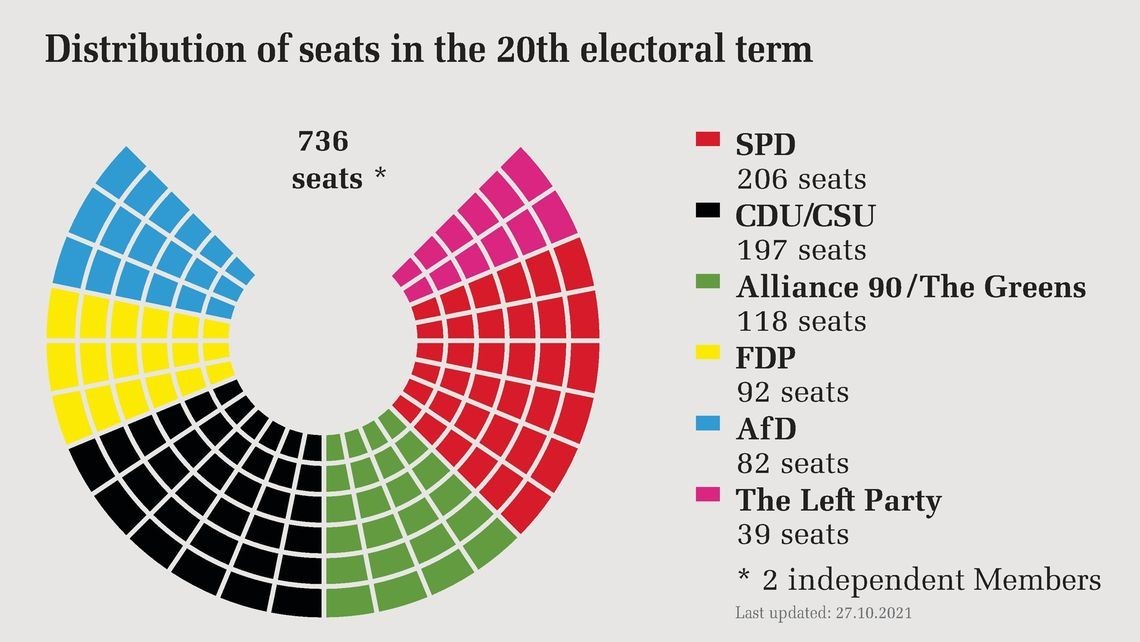

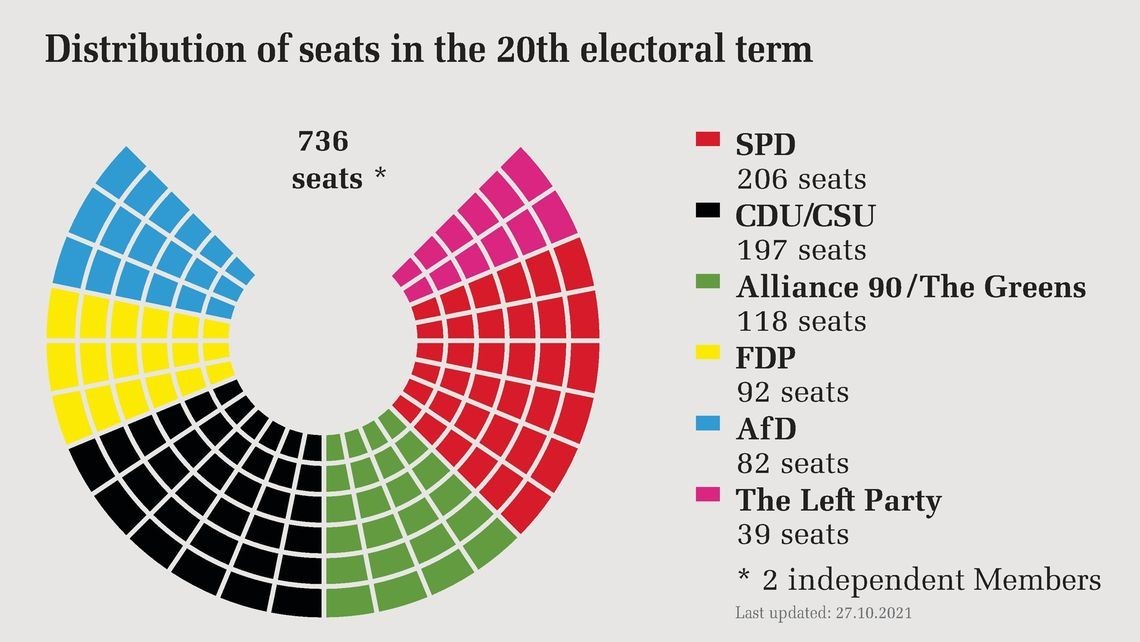

The advantage of keeping up with European policy moves

We ought to keep a much closer eye on German politics. Their leading parties’ ideological evolution has been influencing other European parties over the past decades. Now, Germany’s decisions on matters of economics, trade, migration, finance, industry and constitutional affairs gain singular preponderance in the internal dynamics of other member States and hold sway over the European Union's decisions. Examples abound, either in times of peace or turmoil. The end of the Merkel Era has added new condiments, new expectations, signals that we ought to retain as undeniably best democratic practice to consolidate, especially in party systems undergoing steady fragmentation; party negotiations to form cabinets with professional, procedurally transparent teams; Chancellor Merkel's dignified exit; an impeccable transfer of power laden with symbolic meaning; the inauguration of a new cabinet with a detailed programme of public policy supported by the three parties that comprise it (SPD, Greens and FDP), as well as a foreign agenda for the short term that has been made publicly available.

Source: https://www.bundestag.de/en/parliament/plenary/distributionofseats

Broadly speaking, brief assignment in the German cabinet awarded the Chancellery to the lead (SPD), Vice-Chancellery and Foreign Affairs to the runner-up in the coalition (Greens), and Finance to the third (FDP). Given this hierarchy we are at liberty to say that the liberals’ financial orthodoxy will not override the greater flexibility purveyed by the other two parties, namely with regard to their willingness to review the EU's Stability and Growth Pact (SGP), which is an ongoing conversation in the post-pandemic framework, wherein public debt swells within the Eurozone. Rome and Paris share this willingness. This conversation is relevant to Portugal, shouldering, as it does, one of the largest public and private debt burdens in the world.

To go into detail, the SPD will handle Defence, Interior, Construction and Housing, Health, Labour and Social Affairs, Economic Cooperation. The Greens will take Foreign Affairs, Economy and Climate, Agriculture, Family, Environment and Conservation. Finally, the Liberals will handle Finance, Justice, Transportation and Digitalization, Education. Given this distribution we may gather that each party has gone for the areas that best suit their agenda, which will favour global coordination as it diminishes potential for attrition. In that light, grounds for stability are in place. This is underscored by brisk post-election negotiations (three months shorter than those of four years ago). So the three parties wanted to get to work swiftly and, to that end, they undramatically converged onto a common agenda. This is a good example in Europe, where parties drift away, where the quality of cabinet formation doesn't always shine for its technical acumen, reform ambitions or desire for political stability.

Apparently, German has no such trouble. The coalition appears to have set its sights on stability, and, going by the policy package they’ve agreed on, there's plenty of appetite for reform. Let’s have a look: Voting age down to 16; 20% increase for minimum wage; 400,000 new, affordable dwellings built annually; closure of coal plants by 2030; going from 35% to 80% renewable energy sources by 2030; 25% increase in railroad transportation; reforming nationality laws to accommodate immigration; legalizing cannabis; more assertive relationships with China and Russia; turning the Conference on the Future of Europe into a constitutional convention that can alter the treaty and reinforce EU powers, which would lead to Europe as a federal state; transnational party lists for the European Parliament; vote by qualified majority on EU external policies.

At any rate, one item stands out if we are to assess the scope of such reformist intent. It has to do with the role of the upper house when it comes to passing key legislation. The upper house of Parliament represents the 16 regions. CDU/CSU holds a majority of seats there, which means it will have to come to the negotiating table. Add to that the role of the Constitutional Court and of the Central Bank. These complexify the German decision-making process and also complicate anticipating how Germany will position itself with regard to European matters.

On the day after presentation of the 177-page agreement on governance in Germany (25 November), President Macron and Prime Minister Draghi signed a 15-page strategic agreement at the Palazzo del Quirinale. The fact that this alignment has been in the works since 2018 tells us that we have reinforced cooperation independent of the formal inauguration of the German coalition, where timing is not entirely irrelevant. Most relevant is that it points to Paris and Rome's shared willingness to influence European policy without always having Berlin on board or marching to the same beat. This only underscores the existence of a variable geometry of joint designs in the EU, with risks and benefits for European policy (Weimar Triangle, Hanseatic League, Visegrad Group, "Club Med”, NB6, Friends of Cohesion, Versailles Summit, Three Seas Initiative, Slavkov Triangle).

It is in the light of this communal complexity that the Treaty of the Quirinal must be understood. For starters, because it is the major strategy paper shared by EU-founders in the post-Merkel era. This ambition of setting the course for the community is another avenue for Draghi's rise in the EU after the end of Merkel's tenure. This is valid for potential reforms of the SGP, and helps anticipate the growing curtailment of China's corporate footprint in sectors of strategic relevance, namely technology, agrifood, health or infrastructure. Since February, when he became head of his cabinet, Draghi has already vetoed three Chinese ventures.

Source: www.quirinale.it

But the text of the Treaty includes other highlights, such as more intense consultation at all levels of state apparatus, as well as the creation of new bilateral forums for policy, diplomacy, military, judicial, police, energy, corporate, technological and industrial matters, so as to concatenate and maximize joint positions in the EU, NATO and other organizations. Constant references to "strategic European autonomy” in those domains, as well as to the realization of an economic and monetary union, are seen as support to the Euro in the face of external shock and aggressive competition. On the decision-making plane, more frequent resort to qualified majority on the European Council is favoured. The Mediterranean, Sahel, North Africa and Horn of Africa are seen as key strategic neighbours. In addition to annual bilateral summits, there is a provision for the quarterly inclusion of a member of the other state's cabinet in cabinet meetings.

This step now concludes a three-year negotiation cycle which began with Prime Minister Gentiloni. Presently, under the political transition in Germany, where more financial resources are made available to member-States in the wake of the pandemic and decisions made in Brussels in 2020, and given the electoral pressure awaiting Macron during the half-year that France will preside over the EU Council, this Treaty supports the second and third European economies helping them along the right path of European integration, maybe even in better alignment with the new German cabinet than with its predecessor on many community issues, such as the realization of a true and effective union for health, indispensable reforms to asylum policies, revising SGP rules (at a time when 60% of Eurozone economies hold public debt in excess of 100% of their GDP), the consolidation of a common energy market with greater autonomy and less accommodating of Chinese interests, and greater efficacy in investment policies for Africa.

All these issues are crucial to the near future of the European Union and also to Portuguese interests. They may entail accelerated revision of Treaties, even more glaring blockages by countries wary of intergovernmental mechanisms, with all the issues they’ve been placing in the way of good community decisions, the likes of which one could witness during the pandemic. At any rate, countries that feel at ease about stronger European integration, or those that present favourable internal consensus, need to openly discuss inherent risks and benefits. Such a conversation must take into account not only the political system but also corporations and citizens. Corporations may be better equipped to anticipate decisions stemming from political alignments in Europe, knowing its strategists’ thinking in detail and, correctly interpreting the signals they put out, may plot with a greater degree of accuracy their strategic action plans, reducing risk and maximizing opportunities. They may support, if their scope allows it, exports to promising markets or untapped potential, siding with other companies on projects at scale in priority geographies for the main European capitals, as is the case in Africa, where we can contribute with knowledge that stands out and makes a difference, but focus always on Berlin's Paris’s, Rome’s, and Madrid’s radars. Let us not lose sight of the European Union either which, early in December, announced a competitor programme to the Chinese Belt and Road initiative (BRI), the Global Gateway, which makes available 300 billion Euros until 2027 under a number of schemes. Add to these the 60 billion dollars the US launched in 2019 by the US, Australia and Japan, the Blue Dot Network, the trillion-dollar internal investment package in the US, Build Back Better, which will also compete against the BRI, launched by the G7 last July, with an expected pool of 40 trillion dollars by 2035, and you will understand the magnitude of the amounts earmarked to influence global infrastructure, mobility, digitalization and renewable energy networks. Whoever slices this into the thinnest layers will enjoy a tremendous competitive edge over the next few years.

The complexity of matters that daily cross desks of corporate managers requires new ways of looking at the same problems. The more in-depth of a diagnosis you can make, the more profitable the right decision can be.

Bernardo Pires de Lima was born in Lisbon in 1979. He is a research fellow at the Instituto Português de Relações Internacionais (Portuguese Institute for International Relations) within Nova University of Lisbon, international policy analyst at Portuguese TV network RTP and radio station Antena 1, political consultant to the President of the Portuguese Republic, chairman of the Curators Council of the Fundação Luso-Americana para o Desenvolvimento (Luso-American Development Foundation), and an author, having published, among other titles, A Síria em Pedaços, Putinlândia, Portugal e o Atlântico, O Lado B da Europa, and Portugal na Era dos Homens Fortes. He has been a visiting fellow at the Center for Transatlantic Relations at Johns Hopkins University in Washington DC, associate researcher at the Portuguese National Defence Institute, columnist for newspaper Diário de Notícias and a commentator at TV network TVI. Between 2017 and 2020, he led the political risk and foresight practice at FIRMA, a wholly Portuguese investment consultancy. He's lived in Italy, Germany and the US, but he keeps coming back to Portugal.

Disclaimer: Bernardo Pires de Lima, research fellow with the Portuguese Institute of International Relations (Instituto Português de Relações Internacionais) at Nova University of Lisbon.

The views, thoughts and opinions expressed herein belong solely to the author and do not reflect the official positions or policies of, or obligate, any institution, organization or committee he may be affiliated with.

Bernardo Pires de Lima was born in Lisbon in 1979. He is a research fellow at the Instituto Português de Relações Internacionais (Portuguese Institute for International Relations) within Nova University of Lisbon, international policy analyst at Portuguese TV network RTP and radio station Antena 1, political consultant to the President of the Portuguese Republic, chairman of the Curators Council of the Fundação Luso-Americana para o Desenvolvimento (Luso-American Development Foundation), and an author, having published, among other titles, A Síria em Pedaços, Putinlândia, Portugal e o Atlântico, O Lado B da Europa, and Portugal na Era dos Homens Fortes. He has been a visiting fellow at the Center for Transatlantic Relations at Johns Hopkins University in Washington DC, associate researcher at the Portuguese National Defence Institute, columnist for newspaper Diário de Notícias and a commentator at TV network TVI. Between 2017 and 2020, he led the political risk and foresight practice at FIRMA, a wholly Portuguese investment consultancy. He's lived in Italy, Germany and the US, but he keeps coming back to Portugal.