Global Risk Perspectives - Monthly insights on geopolitics, trade & climate

Back to articlesBernardo Pires de Lima

15.07.2021

Too big for Europe, too small for the rest of the world

The political moment in Germany is significant enough to warrant further analysis. On the one hand, the 26 September parliamentary election will be the first post-war poll where the incumbent chancellor will not seek another term in office. Such a cycle coming to an end carries additional weight because we're talking about Angela Merkel, who's been in power for 16 years. On the other hand, we might witness, for the first time in German history, the end of the partisan duopoly shared by CDU (Christian Democrats) and SPD (Social Democrats), as polls point to the Green Party as the prospective number two. No less important, this is Germany we're talking about. The country with greater say in the European Union, the one that can push impossible initiatives or stall others without argument. The coalition that comes out of the upcoming election will impact post-Covid European stability, any reforms to the Euro, changes to budget treaties, driving reindustrialization for the community and reaching "strategic autonomy” from China, USA and Russia. Or the opposite of all that. So it is worthwhile to take at Germany’s track record in the recent past and reflect on what may come.

Angela Merkel's legacy

The country Angela Merkel has been leading since 2005 can be defined via two significant aspects. The first one would be a direct consequence of implementing the Euro, the most developed federalist instrument of European integration, and one of the two elements to assure Europeans (mainly France and the United Kingdom) that the two Germanies, East and West, would reunite in a controlled, non-threatening fashion; the other was that the reunion would take place under NATO's accommodating wing. The monetary union forged in Maastricht was not intended as German diktat to dominate Europe but a European strategy to contain a reunited Germany. Mitterrand, who opposed this reunion, bound Berlin to the path of integration, on which Paris was already set. Although the Euro's inception owed to political choices, it did, at any rate, become a preponderant factor in Germany’s economic ascent — bolstering its export capacity and trade surplus, bases for the political muscle that Europe now deploys.

The second aspect pertains directly to structural reforms furthered by the SPD/Green cabinet (1998-2005), which, among other things, let the labour market become more flexible, and allowed social security reform and tax cuts, but also cutting on retirement pensions and unemployment benefits. Many Germans called these developments, arising out of Agenda 2010, the greatest blow against the post-war welfare state. Unions took to the streets in major German cities, organizing massive demonstrations. German society felt the violent impact of these reforms. The outcome of the 2005 election turned out to be the best one could hope for, pushing CDU/CSU and SPD into a large coalition that would then steer the reforms. In that light, Merkel's leadership has only been sustainable because those reforms adapted the German economy to the impacts of economic globalization, the rise of non-European powers and the sluggishness of several Eurozone economies. Merkel's virtue, comparable to Tony Blair's after Thatcher and Major (she achieved three consecutive parliamentary majorities), was to not break with, or blot out her predecessor's reforms. Had she done so, Germany would not respond the same to the global crisis that followed the Lehman Brothers collapse. That's why Merkel getting re-elected in 2009, 2013 and 2017 comes as no surprise. Germans like predictability and trust her leadership model.

The Germany that rises anew over the two post-reunion decades has demonstrated more capability to face major European challenges than most Member States. On her second term, in a coalition with the FDP liberals, dealing with a stalemate in treaty negotiations, an international financial crisis, sovereign debt in Europe, the Ireland, Greece and Portugal bailouts, and the imminent collapse of the single currency, Angela Merkel stepped up as a leader on all those fronts. Not so much to mint herself the new European Tsar — though she does feature a portrait of Catherine the Great in her office — but to safeguard the Euro as a guarantee for that monopolar German moment. If the single currency was one of the means of growth in Germany, there is no reason to end the experiment. Even if it means driving down standards of living for many European states under financial assistance.

In other words, it's not so much the German Chancellor defining an articulated plan for Europe as it is this ascending Germany (hand in glove with the Constitutional Court's political centrality) that conditions Merkel's decisions. Governing nuance aside, another chancellor would have first seen to German interest than that of other European nations. This is not to absolve Ms. Merkel of her errors, exaggerations, stubbornness, mistakes, obsessions and the damage she's caused throughout this endless European crisis — no, merely a line of thinking that intends to highlight another impassable political front (German voters, Teutonic institutions and the historical moment in Germany) and less of a personal, isolated reading of German's internal context. The learning that arose from those errors was experienced during the management of the pandemic crisis.

Coalitions recur in post-war German history. Only once after WWII was there a one-party majority in parliament (CDU, from 1957 through 1961), and even then Adenauer's party had to run, as usual, with the Bavarian CSU in a pre-election coalition. Going back to Merkel, since 2005 she spent 12 out of 16 years governing through a "major coalition”, which is to say, with the SPD. Before that, Schroeder's reforms, which healed the "European Patient”, as the Economist called it, had been supported by the CDU. In 2005, the two parties made the union official and, from 2009 onward, even outside of government, the SPD further supported Ms. Merkel's policies than did FDP, with which the chancellor entered into a coalition for four years.

Pragmatism has been another ingredient in Merkel's European policy. It helps that she ironed out the kinks in the relationship with Paris when the time was right, especially over the past two years with President Macron, engaging a wider swath of Member States, and that she enjoys a close relationship with the current president of the European Commission. But such leaderships happen because forces within the great German coalition have aligned in a different way. The SPD team in Finance has relinquished some tenets of its financial orthodoxy regarding the EU. The Minister of Foreign Affairs and the Chancellor have indicated they see German interest coalescing with European interests. The economy may now rely on a heavyweight like the CDU that can support outsized community plans for rapid recovery in the common market, and the health sector is led by an ambitious CDU politician who, propelled by the sector’s financial surplus, has tried to steer clear from the path of error and avoided creating entropy in the coalition. At the top, President Steinmeier has contributed quality and sensibility, investing this delicate European moment with the historic tone demanded of decision-makers and content befitting the solutions required. It is this social-democrat consensus which many would call milquetoast centrism, of which Merkel is the hub. Starting with the refugee crisis in 2015, she's been sustaining Germany and contributing to a European reaction one would deem rather more constructive than the response to the prior financial crisis.

Rise of the Green Party

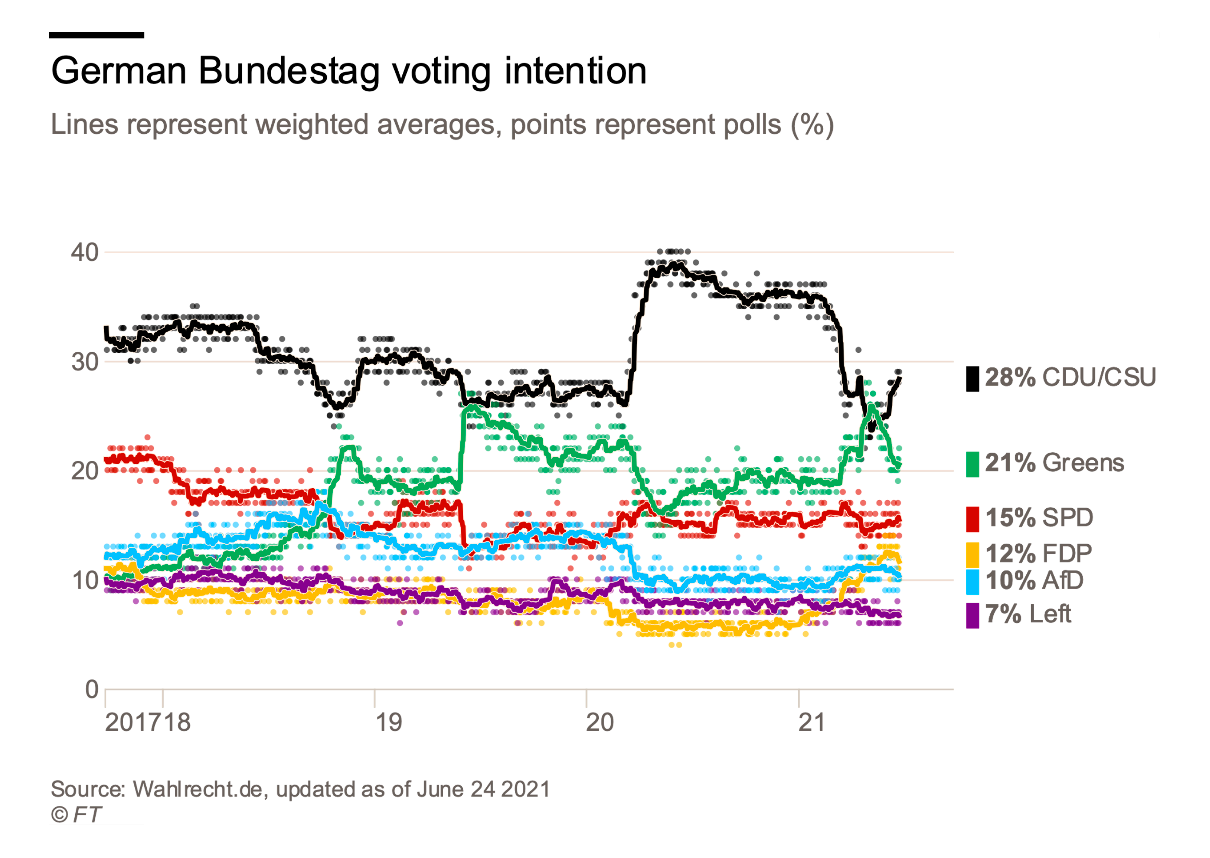

In 2005, Angela Merkel became the first woman elected to the German Chancellorship and the first head of government from East Germany, as well as the youngest. In 2021, the novelty factor doesn't have such a clear protagonist. Rather, it has congregated around the lightning rise of the Green Party which, over the past few years, have become the number two party in German polls, and even number one at times. Elbowing their way into the CDU/SPD duopoly, they have shaken German politics to the core, but this also carries strong transformative potential to their European strategy and even their relationship with the world's superpowers.

Few may now recall that the current German cabinet took six months to begin working in an official capacity when the September 2017 parliamentary election gave Merkel her fourth consecutive victory. Few may now remember, but the Green Party was the first to agree to negotiations with CDU in order to form a coalition, but such a coalition did not come to pass. These two facts tell us that, on the one hand, it may be good to prepare for a hiatus after the next election, taking into account the balanced outcomes suggested by polls, which were not so four years ago; on the other hand, that the Greens do not only have a honed sense of practicality but also that, these days, such practicality makes them more competitive in the quest for political power.

It wouldn't be redundant to state that European politics experienced changes in 2020. Despite the pandemic, though maybe also because of it, investment in climate transition remained steadfast. Despite the pandemic, though maybe also because of it, priority given to digital transformation dictated the pace of economic reform and of the recovery plans that have been set in motion. Indeed, a part of the funds made available, regardless of scheme or schedule, is intended for expansion of environment-friendly infrastructures — in mobility, power generation or housing, you name it. Much on account of the pandemic, Europeans agreed on a joint debt issue mechanism that wouldn't have gone forward without the current crisis. That would have seemed unimaginable. We can also add that the debate on new instruments and powers for the EU gained traction over the past year, be it in public health, the tax domain, its strategic autonomy, climate ambitions, or the role the CEB must play. In truth, if we add openness to refugees, we can conclude that all those dynamics are near and dear to the Greens’ agenda. They're the most pro-European faction in the Bundestag, which not only validates the pertinence of their positions, as far as voters are concerned, but also pushes their authentic acuity to the front lines of European politics. I would dare say Angela Merkel unwillingly became the political godmother and patron to the growth of the Green Party.

They’ve benefited from such patronage on the European plane through the dynamics I described above, and gained non-negotiable counterpoints against China or Russia, especially when they opposed Nord Stream 2. If the party proves able to explore an alternative path that will secure allies in Europe and mostly in Washington, that will lead to deep change in European politics. Over in Germany, the double disappointment served up by Merkel's chosen successors, Annegret Kramp-Karrembauer e Armin Laschet, and the latter's difficulties in mobilizing forces, along with the cacophonous management of the pandemic over the past months, added to instances of corruption in parliament, have facilitated the rise of the Greens as obvious sanctuary to centre-left voters weary of the SPD and centre-right voters orphaned by Merkel. Annalena Baerbock being put forward as prospective chancellor may prove smart. She could give the Greens a powerful boost leading to consolidation of a large social-democrat basis up until the election — a vote for the novel, though novel doesn't mean flash in the pan; for an agenda that time has validate, and pragmatism that does not become malleable; for a cosmopolitan programme that does not neglect rural issues; with the world in its sights, but a local perspective as well; plus the power of a new generation added to competence.

Green leadership has been pragmatic above all. The party currently sits in 11 out of 16 state governments. Ten in geometrically varied coalitions as junior partner (with CDU, SPD, FDP and Die Link) and leading one (Baden-Wurttemberg) with CDU. Their economic programme, quite unlike the one from the 1980s, converges with digital transformation in industries and an environmental outlook. They have taken on pro-business commitments by creating an Economic Council within the party to maintain close dialogue among party leaders, MPs, economic actors and powerful industrial federations. The purpose is to normalize their credibility with key voter groups, present themselves as stewards and trustees of the voter confidence held by the centrist wing of the CDU, and bring to the conversation on market economics the regulatory note the SPD has failed to impart. So the Greens of today are wholly for the market economy, but they strive to put an end to privileges and monopolies to ensure that the market runs with greater democratic efficiency and more social justice.

Effects on the European Debate

With several outcomes hanging in the balance, and roles such as Chancellor, Minister of Finance, of Foreign Affairs, or Energy, one should expect Greens’ moves in German politics to have repercussions on European politics. The first is that the federalist approach will gain new traction. It may not get called ‘federalist’, but the defence alone of new instruments for the EU follows that design. Among them, ending the debt ceiling in Germany, which will impart a new dynamic onto the current debate around the review of the Stability and Growth Pact; establishing permanence for pandemic emergency frameworks like SURE; put an end to unanimous votes on EU decisions on matters of external policy and security; uphold a higher minimum wage and unconditional basic income; defending the 30-hour work week; diverge on NATO's goal of earmarking 2% of GDP for Defence; oppose China's Belt and Road Initiative, contrary to Huawei 5G contracts and for limits on bilateral relations as response to human rights violations; and, by 2030, attain 500 billion euros in public spending in Germany, pushing it to the forefront as a driver of green reindustrialization in Europe and a hub for regulated technological transformation.

Lawmakers, entrepreneurs, investors and analysts who naturally place Germany at the heart of European policy must immediately begin to assess the consequences of Green ascension and the end of the Merkel cycle. Going off polls and recent regional elections, there seems to be life beyond nationalists’ aggressive superficiality.

Disclaimer: Bernardo Pires de Lima, research fellow with the Portuguese Institute of International Relations (Instituto Português de Relações Internacionais) at Nova University of Lisbon.

The views, thoughts and opinions expressed herein belong solely to the author and do not reflect the official positions or policies of, or obligate, any institution, organization or committee he may be affiliated with.

Bernardo Pires de Lima is Political Adviser to the President of the Portuguese Republic. He is also a Research Fellow at the Portuguese Institute of International Relations, IPRI-NOVA, an international politics analyst for the national Portuguese television channel RTP, for radio station Antena 1 and the Portuguese daily Diário de Notícias. He chairs the Luso-American Development Foundation’s (FLAD) Curators Council and has been a Research Fellow at the Johns Hopkins Center for Transatlantic Relations in Washington DC and at the National Defense Institute in Lisbon, Portugal. He has penned eight books on contemporary international politics, the most recent being Portugal na Era dos Homens Fortes: Democracia e Autoritarismo em Tempos de Covid (Portugal in a time of strongmen: Democracy and authoritarianism in a time of Covid), published by Tinta-da- China in September 2020.